Engineers from the University of Illinois have used

nanotechnology to model a new membrane that can filter salt from

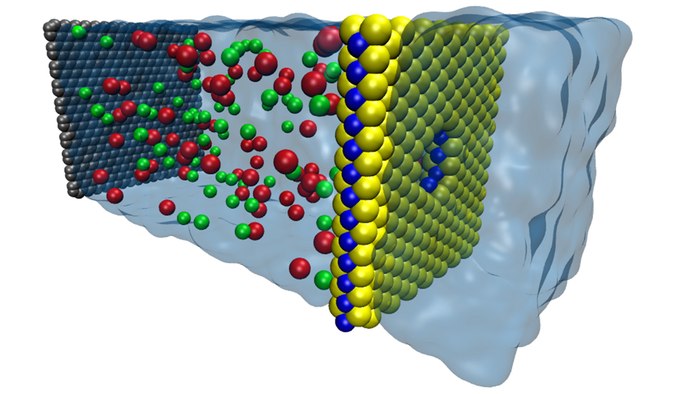

seawater at higher volumes than ever before. The membrane is made

from a nanometer-thin layer of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2)

studded with tiny holes called nanopores. By "pulling" clean water

through itself while filtering out salt and other compounds, the

membrane has the potential to make desalination plants much more

energy-efficient.

Desalination plants that convert high volumes of seawater into fresh water now operate in more than 150 countries, according to the International Desalination Association. Most rely on a process called reverse osmosis, which involves pushing water through a membrane to filter out salt and other impurities.

"Reverse osmosis is a very expensive process," study leader, professor Narayana Aluru, says. "A lot of power is required, it's not very efficient and the membranes fail because of clogging. So we'd like to make it cheaper and make the membranes more efficient so they don't fail as often. We also don't want to have to use a lot of pressure to get a high flow rate of water."

Replacing the desalination industry's widely-used plastic filtration membranes with extremely thin membranes is not a new idea – researchers have been experimenting with new materials and techniques for some time now. However, the materials studied so far have varied widely in the way they interact with water.

The engineers used the university's Blue Waters supercomputer to discover that a single-layer sheet of MoS2 provided the best performance over current contenders such as graphene. In fact, the researchers found the MoS2 membrane was able to filter through up to 70 percent more water than graphene membranes.

MoS2 is made up of one molybdenum atom sandwiched between two sulfur atoms, so a sheet of MoS2 sees a single atom-thick layer of molybdenum sandwiched between a coating of sulfur atoms on either side.

The researchers created tiny pores in the sheet, exposing rings of molybdenum around the center of each pore. Due to the inherent water-attracting properties of molybdenum, the pore acts as a nozzle that draws water through.

"The molybdenum in the center attracts water, then the sulfur on the other side pushes it away, so we have much higher rate of water going through the pore," said graduate student Mohammad Heiranian, the first author of the study. "It's inherent in the chemistry of MoS2 and the geometry of the pore, so we don't have to functionalize the pore, which is a very complex process with graphene."

According to the team, MoS2 is a very robust material, so even a very thin sheet can hold up against the pressures and water volumes needed by desalination plants.

It's still a fairly new material, but the researchers believe that manufacturing techniques – and presumably costs – will improve as the demand for MOS2's high-performance properties increase.

Fouling, or clogging of the pores, is a major issue for membranes used in desalination, particularly for plastic filters. So the next step for the team is to develop further tests to explore the membrane's viability as a desalination filter, and to test its rate of fouling.

The team's research appears in the journal Nature.

Source: University of Illinois