Federally Recognized: Métis, Other Non-Status Indians Rejoice at Canada Supreme Court Ruling

Métis and non-status Indians are Indians, “and it is the federal government to whom they can turn.”

That is how Justice Rosalie Abella put it, speaking for a unanimous Canadian Supreme Court on April 11. This decision, she said, puts an end to the passing the buck back and forth between provincial and federal governments as to who is responsible. The Court “recognized that Métis and non-status Indians have no one to hold responsible for the inadequate status quo.” Now they have.

It was back in 1999 that Saskatchewan Métis activist and leader Harry Daniels got the court case started, but it took until now to bring it to a successful conclusion. Daniels died in 2004, but his son Gabriel was added to the case as one of the appellants.

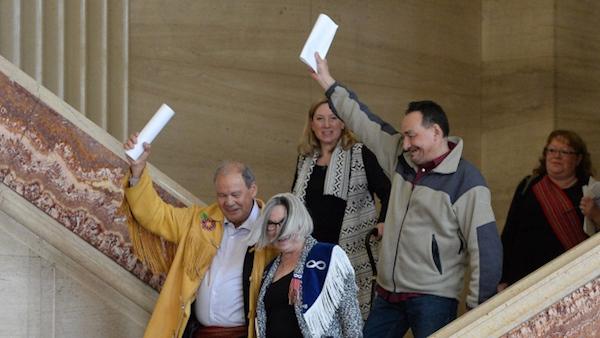

“I’m overwhelmed and ecstatic,” Gabriel Daniels said, “and I wish my father were here to see this. He’d probably do a jig right now.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau greeted the decision, calling it “a landmark ruling that will have consequences and impacts right across the country.”

Another Daniels son, Alex Wrightman-Daniels, joined in the jubilation.

“His lifelong dream to find equality has finally been reached,” he said of the elder Daniels.

Métis leaders also hailed the decision.

“This is a significant victory for the Métis Nation. It will facilitate reconciliation between Canada and Métis communities from Ontario westward,” said Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) President Gary Lipinski in a statement.

In addition the decision clears up some muddying of jurisdiction, the Métis National Council (MNC) noted.

“This decision ends the federal government’s longstanding discrimination and non-recognition of the Métis people and the elected body that represents the Métis Nation—the Métis National Council,” said MNC President Clément Chartier in a statement, adding that it ends “the jurisdictional tug-of-war in which these groups were left wondering about where to turn for policy redress.”

The victory goes beyond Métis.

"This is a great day for over 600,000 Métis and non-status Indians," Dwight Dorey, national chief of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, told CBC News. "Now hopefully we will not have to wait any longer to sit at the table."

First Nations and Inuit alike heralded the ruling as a victory for all Indigenous Peoples.

“Today’s decision is yet another sign that colonial laws are crumbling,” said Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde. “It is time to build a renewed nation-to-nation relationship founded on inherent and Treaty rights as recognized in Canada’s Constitution and the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

The Southern Inuit of NunatuKavut, in southern and central Labrador, hailed not only the equal access to programs but also the potential for forging of a new relationship with the Canadian government.

“From this moment forward, we shall never be excluded or forgotten again,” said NunatuKavut Community Council President Todd Russell in a statement. “This outstanding decision recognizes our humanity and dignity as Indigenous people in Canada. Now, we can truly continue to build a nation-to-nation relationship with the Government of Canada and gain the recognition that we deserve and have been fighting for generations.”

All admitted that this decision is just the beginning. It provides the framework, but Métis and non-status Indians must still negotiate and advocate in order to define what constitutes indigenous status, an issue that has been under contention for years.

RELATED: Métis to Government: We’ll Determine Our Own Identity, Thank You

Canada Reconsidering Métis-Definition Contract

While the Abella decision, which traced the history of the meaning of the term “Indian” in Canadian law, came down firmly on giving the federal government a fiduciary responsibility for Métis and non-status Indians, it deliberately left undefined who is Métis and who is non-status. Historically, the Métis were the offspring of French fur traders and Indian mothers. They established settlements in the prairie provinces, some of which exist to this day. Later, some white-Indian offspring in the Maritimes also identified as Métis, but with different cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

In addition there’s the question of residency. Some of the Métis live in settlements, and they will now be in a position to negotiate land claims. What happens when they move away from their original settlements? How do they differ from other people in intermarried unions? In short, who is and who is not a Métis person today, entitled to federal fiduciary protection and all the benefits due Indians? Abella suggested in her ruling that “this is a matter to be determined on a case-by-case basis.” But the criteria are at best unclear.

Many Canadian Indians have some white forbears. Back in 2013, the federal government and the Federation of Newfoundland Indians signed an agreement to enroll Newfoundlanders who had Indian ancestry into the Qalipu Mi’kmaq band, a band without a reservation. At that time, Greg Rickford, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs, stated that both the federal government and the Federation of Newfoundland Indians expected no more than 12,000 applicants, but 100,000 sought status.

RELATED: Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation Band Officially Created in Newfoundland

The concept of non-status must also be defined. Over many decades, people lost status for various reasons, and their descendants also came to lack status. For a long stretch of time, if a woman married a non-Indian she lost status. A Supreme Court decision put a stop to that, but her children might not have status. In some cases an Indian woman would choose to cohabit with a white spouse without marriage in order to protect the status of any children. At one time, becoming a clergyman would terminate status, as would graduation from university. Some men, particularly in the military, voluntarily gave up status so that they could buy liquor, at a time when status Indians were not allowed to do so. In short, the definition of non-status has changed drastically over time.

"The consistent narrowing of the definition of 'Indian' in various amendments to the Indian Act created a large population of aboriginal people without Indian status or the rights and entitlements that attach to it—the non-status Indians," explained University of Ottawa law professor Joseph Magnet. "It also includes people of aboriginal ancestry and culture who were never entitled to register in 1876, as well as aboriginal people entitled to register who chose not to submit themselves to the department's control."

RELATED: Attorney: Aboriginal Grandchildren Are Owed $2.7 Billion

Once they have overcome the definition hurdles, Métis and non-status Indians will need to work their way into status Indian programs for health benefits such as medicines, medical supplies, and dental and vision care. They will also have to find their way into federal support provisions for aboriginal post-secondary education. But such concerns themselves can be seen as a sign of progress, given that the court ruling on status has laid the foundation for even considering those issues.

“Today’s Supreme Court decision has given us much-needed clarity on the issue of responsibility which has hung over us for generations,” said Dorey in a statement. “We see clearly today in what direction we and our government partner should be heading. Now it’s time to begin the hard work that needs to be done to help pave the path forward for our people.”

RELATED: Métis in Canada Demand Harper Meeting as Court Upholds Status Ruling

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/04/20/federally-recognized-metis-other-non-status-indians-rejoice-canada-supreme-court-ruling