Ojibwe Cosmos: Mercury in Retrograde, Earthly Stardust and Intricate Stellar Maps

Even though a sprinkling of snow fell just this Thursday in northern Minnesota, any arrows shot earlier at Wintermaker apparently have hastened his final departure from the sky. But the rise in the night of Curly Tail, the Great Panther of spring, could bring the threat of floods and dangerous, uncertain travel.

Long before Europeans brought over their Greek monikers for the constellations, Native cultures already had named their sky people. And those faraway relatives helped them to understand their world and how to survive in it.

For the Ojibwe, the constellations of Mooz (Moose), Biboonikeonini (Wintermaker), Mishi Bizhiw (the Great Panther) and Nanaboujou (the original man of Anishinaabe narratives), heralded the arrival of fall, winter, spring and summer.

The Dakota/Lakota people might see Keya (Turtle) and Nape (Hand) above them at different times of year, while the Diné people had noted and identified “Halley’s” Comet as So' Bitsee' Nineezí (Star with a Long Tail) centuries before there was an Edmond Halley.

The Polynesian people knew the stars so well that navigation via their star compass, which divides a 360-degree view into 32 star houses, has been revived by the Polynesian Voyaging Society to promote the art and science of the culture. Christopher Columbus certainly could have benefited from their knowledge, developed thousands of years before he took his journey of supposed discovery.

Boarding schools curtailed pursuit of traditional science, and fatal epidemics such as smallpox nearly wiped out some orally kept wisdom before it could be properly passed forward. But energetic Native scientists and artists are unearthing and reviving this almost-lost sky knowledge.

“Absolutely, I do see a new interest in indigenous knowledge,” said Michael Wassegijig Price, a longtime Ojibwe educator. “Natives and non-Natives alike are pursuing those avenues in many fields—not just astronomy, but also climate change and science, and in the arts and culture as well.”

When he taught the extremely popular Indigenous Astronomy course at Leech Lake Tribal College, Price added, “I was teaching the biggest class at the college.” Price also spoke at a well-attended Smithsonian Institution’s 2012 series on Cultural Astronomy.

Price, former director of college programs for the American Indian Science & Engineering Society (AISES), has been one of those trying to recreate ancient knowledge.

“It was like putting together a broken vase, putting our knowledge back together again after residential schools,” he said. “In some places, there are going to be pieces missing permanently.”

Ojibwe elder, educator and artist Carl Gawboy has been a wellspring resource for recovering Anishinaabe sky knowledge, thanks to the teachings of his father and to written and oral source materials.

“I used many of these sources and then compared them with what my father said,” explained Gawboy. “Sometimes it was a perfect match, and sometimes it was a different planet.”

Gawboy, along with Ron Morton, a professor emeritus from the University of Minnesota Duluth, has written a three-book series mingling modern science and traditional Ojibwe knowledge of geology and, most recently, astronomy.

In Talking Sky (Rockflower Press, 2014), Gawboy recalls his father’s pointing out the local pictographs at Ham Lake as depictions of the seasonal change of constellations. Those constellations, in turn, reflected traditional teaching narratives. Take the tales of Wintermaker. This winter-rising Ojibwe constellation incorporates the star grouping popularly known as Orion, but extends beyond it. Winter brought hard times on traditional communities, but also welcome times of gathering together for storytelling and of making or repairing tools on which survival depended.

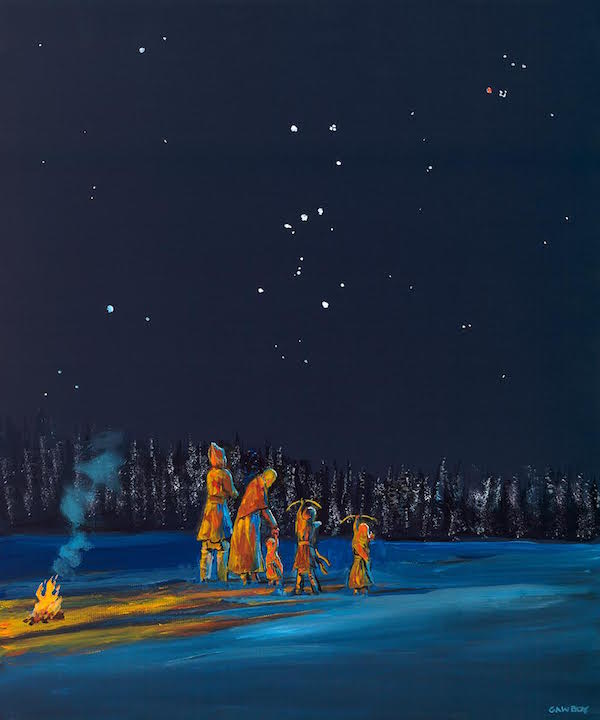

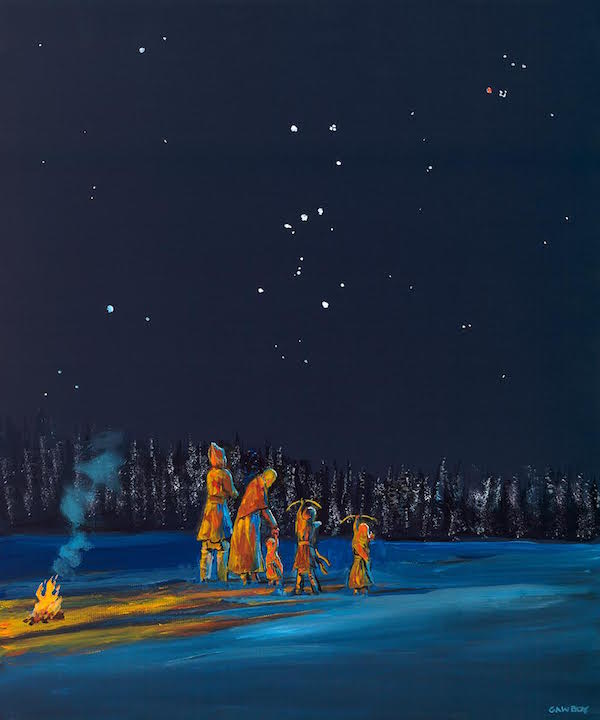

By late March and early April, though, people were glad to see Wintermaker departing from the night sky. Traditional stories tell of tricking Wintermaker into leaving; Nanaboujou feasted him until he started sweating, melting all his winter works. Sometimes parents encouraged children to shoot arrows at the constellation, hastening the end to winter. Gawboy depicted that tradition in one of his paintings.

Gawboy has become involved in another project spreading Native knowledge about the sky and earth and broadening respect for the science practiced by traditional peoples. Native Skywatchers—Earth Sky Connections, a series of courses that teach how to make art in relation to Earth and the stars, was created in 2007 by astrophysicist and St. Cloud State University Professor Annette S. Lee, mixed-race Dakota-Sioux. Lee has traveled as far as Africa for conferences exploring and reviving indigenous knowledge of astronomy and earth sciences.

“I’ve gone all over the nation, and all over the world, and people are impressed,” she said. “There’s no one person who has it all, but it’s not so far gone that it’s lost. It forces collaboration.”

Part of Lee’s genius, perhaps because she herself is an artist, has been bringing together artists and scientists. The outgrowth has been two star map guides—one Ojibwe and one Dakota-Lakota. Her group is now developing a Cree star map at the request of a community in Canada.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/04/02/ojibwe-cosmos-mercury-retrograde-earthly-stardust-and-intricate-stellar-maps-164002