Meet Ötzi: The Most Fascinating Mummy Ever Found

Ötzi was amazingly well preserved when he was unearthed, and as a result, an insightful view of prehistoric life has emerged in the wake of his discovery. Here are some of the most incredible things that we've learned so far from the famous iceman.

You might not expect a 5,300-year-old mummy to be all tatted up — but Ötzi is. Four thin, black lines, stacked on top of each other, bring the total number of Ötzi 's tattoos to 61, according to a study published in 2015.

Ötzi's tattoos are no secret: Even the hikers who discovered him in the Italian Alps in 1991 noticed he had markings on his skin. But researchers have disagreed about the number of tattoos on Ötzi’s body for years, and "we decided it would be important to have a clear number of the tattoos" going forward, Albert Zink, the 2015 study's senior researcher and head of the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman at the European Research Academy in Italy, told Live Science. [Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Secrets About Otzi the Iceman]

To investigate, the researchers used technologies developed for the art world: a camera with specialized lenses that can determine whether an artist painted over another painting on the same canvas. The various lenses can capture different wavelengths of light, ranging from ultraviolet light at 300 nanometers (billionths of a meter) to infrared light at 1,000 nm. (Visible light extends from about 400 nm to about 700 nm.)

All 61 of the tattoos are made of black lines, measuring 0.3 inches to 1.6 inches (0.7 to 4 centimeters) in length and arranged in groups of two, three or four parallel lines, the researchers said. Two of the tattoo groups, one on the right knee and another on the left Achilles tendon, look like plus signs.

"We know that they were real tattoos," Zink said. The tattoos' creators "made the incisions into the skin, and then they put in charcoal mixed with some herbs."

The other tattoos are mostly on Ötzi’s lower back and on his legs, between the knee and the foot. But it's unclear why Ötzi had these tattoos, and whether they had therapeutic, symbolic or religious significance, the researchers said.

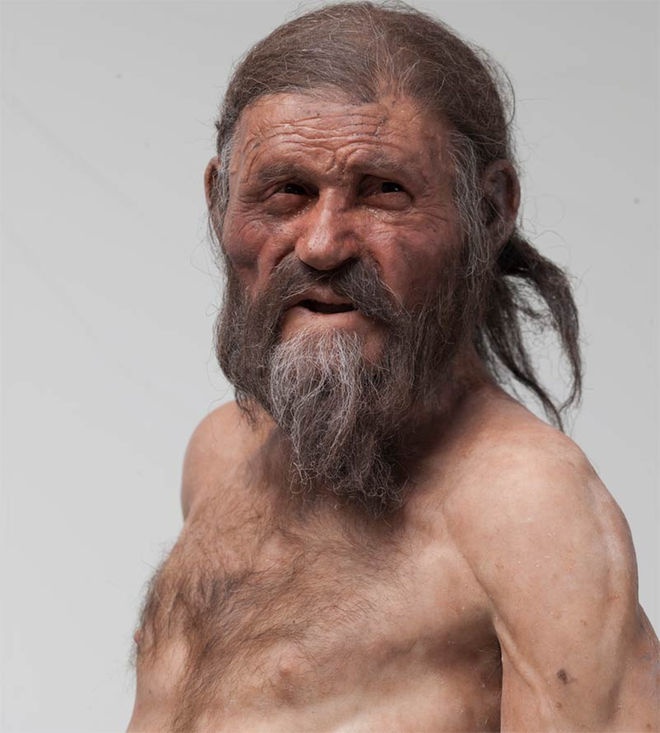

Ötzi has become one of the most-studied ancient human specimens. His face, last meal, clothing and genome have been reconstructed — all contributing to a picture of Ötzi as a 45-year-old, hide-wearing, tattooed agriculturalist who was a native of Central Europe and suffered from heart disease, joint pain, tooth decay and probably Lyme disease before he died.

None of those conditions, however, directly led to his demise. A wound reveals Ötzi was hit in the shoulder with a deadly artery-piercing arrow, and an undigested meal in the Iceman's stomach suggests he was ambushed, researchers say. [Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Secrets About Otzi the Iceman]

A few years ago, a CAT scan showed dark spots at the back of the mummy's cerebrum, indicating Ötzi also suffered a blow to the head that knocked his brain against the back of his skull during the fatal attack.

In the new study, scientists who looked at pinhead-sized samples of brain tissue from the corpse found traces of clotted blood cells, suggesting Ötzi indeed suffered bruising in his brain shortly before his death.

But there's still a piece of the Neolithic murder mystery that remains unsolved: It's unclear whether Ötzi's brain injury was caused by being bashed over the head or by falling after being struck with the arrow, the researchers say.

The study was focused on proteins found in two brain samples from Ötzi, recovered with the help of a computer-controlled endoscope. Of the 502 different proteins identified, 10 were related to blood and coagulation, the researchers said. They also found evidence of an accumulation of proteins related to stress response and wound healing.

A separate 2012 study detailed in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface looked at the mummy's red blood cells (the oldest ever identified) from a tissue sample taken from Ötzi's wound. That research showed traces of a clotting protein called fibrin, which appears in human blood immediately after a person sustains a wound but disappears quickly. The fact that it was still in Ötzi's blood when he died suggests he didn't survive long after the injury.

Ötzi the Iceman may have had a genetic predisposition to heart disease, according to research published in 2014.

This finding may explain why the man — who lived 5,300 years ago, stayed active and certainly didn't smoke or wolf down processed food in front of the TV — nevertheless had hardened arteries when he was felled by an arrow and bled to death on an alpine glacier.

"We were very surprised that he had a very strong disposition for cardiovascular disease," said study co-author Albert Zink, a paleopathologist at the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman at the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano in Italy. "We didn't expect that people who lived so long ago already had the genetic setup for getting such kinds of diseases."

Despite spending years hiking in hilly terrain, it seems Ötzi couldn't walk off his genetic predisposition to heart disease.

"He didn't smoke; he was very active; he walked a lot; he was not obese," Zink said. "But nevertheless, he already developed some atherosclerosis."

The findings suggest that genetics play a stronger role in heart disease than previously thought, he said.

To follow up, the team would like to compare the genetic makeup of other mummies with the state of their arteries, to tease out just how much of a role genetics play in heart disease, Zink said. It would also be interesting to see whether ancient mummies exhibit signs of inflammation, the body's response to infection or damage, that has been tied to heart attacks, he added.

Ötzi the Iceman may have lived thousands of years ago, but he still has living relatives, according to a genetic analysis published in 2013. The 5,300-year-old mummy has at least 19 male relatives on his paternal side.

"We can say that the Iceman and those 19 must share a common ancestor, who may have lived 10,000 to 12,000 years ago," study co-author Walther Parson, a forensic scientist at the Institute of Legal Medicine in Innsbruck, Austria, wrote in an email.

"In that sense, those 19 are closer related to the Iceman than other individuals. We usually think about our families when we talk about relatives. However, these data demonstrate that DNA can also be used to trace relatives much further back in time." [Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Secrets About Ötzi the Iceman]

Parson and his colleagues stumbled upon the Iceman mummy's relatives by accident. The team was studying how the geography of the Alps may have affected the genetics of the people in this region of Europe.

As part of the study, scientists analyzed the genetic material from the male (or Y) chromosome, which is passed on only from the father, in about 3,700 men in the region.

The team found that about 19 men shared a genetic lineage, called G-L91, with Ötzi. It's possible that at least one of these men may directly descend from the Iceman, part of an unbroken line of sons going back 5,300 years.

However, "the chances are so extremely low that I would be tempted to say no," Parson said. "There are just too many other possibilities."

That may not be the last word on Ötzi's relatives. Because the team continues to study the region around the Alps, other long-lost relatives to the Iceman may turn up in future research, Parson said.

Poor Ötzi. Before the Iceman succumbed to a violent attack by members of his own species, a much different sort of creature scorned him — a tiny tick. That's right: Our pal Ötzi had the oldest known case of Lyme disease.

As part of work on the Iceman's genome — his complete genetic blueprint — scientists found genetic material from the bacterium responsible for Lyme disease, which is spread by ticks and causes a rash and flulike symptoms and can lead to joint, heart and nervous system problems.

The analysis, which was performed in 2012, also indicates the Iceman was lactose intolerant, predisposed to cardiovascular disease, and most likely had brown eyes and blood type O.

To sequence the Iceman's genome, researchers took a sample from his hip bone. In it, they looked for not only human DNA — the chemical code that makes up genes — but also for that of other organisms. While they found evidence of other microbes, the Lyme disease bacterium, called Borrelia burgdorferi, was the only one known to cause disease, said Albert Zink, a study researcher and head of the European Institute for Mummies and the Iceman at the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano (EURAC) in Italy.

"Our data point to the earliest documented case of a B. burgdorferiinfection in mankind. To our knowledge, no other case report about borreliosis [Lyme disease] is available for ancient or historic specimens," Zink and colleagues write in an article published on Tuesday (Feb. 28) in the journal Nature Communications.

Discovering evidence of Borrelia is an "intriguing investigative lead," said Dr. Steven Schutzer, an immunologist at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-New Jersey Medical School.

"Now we know what we want to look for, now that we know there is a possibility of that being here, we can do a very targeted approach that looks for Borrelia," Schutzer said.

Lyme disease is transmitted by ticks in North America and Eurasia. It was first found in the United States in Connecticut in the mid-1970s; a similar disorder had been identified in Europe earlier in the 20th century.

Ötzi the Iceman could have used a dentist. The amazingly preserved Neolithic mummy had tooth decay, gum disease and dental trauma, according to research published in 2013 in the European Journal of Oral Sciences.

The iceman mummy's grain-heavy diet was what took a toll on his dental health, researchers concluded.

"It's surprising how bad condition he is in," said study co-author Frank Ruhli, a paleopathologist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. "We have the whole range of disease pathologies you can imagine."

Despite all the poking and prodding that Ötzi has endured, this was the first time scientists looked at his chompers. Ruhli and his colleagues used a CT scanner to analyze the condition of Ötzi's teeth. They found that the ancient farmer had several cavities, likely caused by his carbohydrate-rich diet.

Ötzi also showed severe wear of his tooth enamel and severe gum disease. Hard minerals in milled grains abraded the surface of his teeth and gums, exposing the bone below and making the roots loose. Similar wear-and-tear is found in the teeth of Egyptian mummies who ate milled grains, Ruhli said.

"This is like a sandpaper acting on your teeth," Ruhli told LiveScience. "In another five to 10 years, he certainly would have lost some of his teeth."

As a result of his poor dental health, Ötzi would have felt pain when eating hot or tough foods, Ruhli said.

Ötzi also showed evidence of trauma to his front right incisor from being struck, either in a fight or an accident.

Ötzi's dental problems show the results of switching from a strict hunter-gatherer diet to an agricultural one, Ruhli said.

"Hunter-gatherers were depending on meat and berries, whereas [Ötzi] had processed food," Ruhli said. "The processing added a bigger variety of food but also impacted the quality of the teeth."