Artificially Sweetened: How Politics Massaged the Science in the New Dietary Guidelines

The federal government just released a new set of dietary guidelines, and as always, they’re a work of both science and politics. They include controversial changes: for instance, sugar now has a limit, and cholesterol does not. Here’s your guide to what’s new, what isn’t, and where the experts disagree.

These dietary guidelines are updated every five years because nutrition and medical science evolves. Not because your body has started digesting food differently, but over time we get a better understanding of how our bodies work. When new research suggests that older wisdom might be wrong, it’s tempting to throw up our hands, wonder if nutrition is too confusing, and decide we’re just going to eat whatever we want and call it moderation. But that Coke doesn’t get any healthier because you’ve decided not to care about it.

You should definitely read the guidelines, but be aware of what’s controversial. Use your critical thinking skills and make your own decisions. Perfect scientific truth about nutrition isn’t a realistic goal: there just aren’t simple experiments that can answer big questions like whether it’s okay to have bacon every morning. So a government committee takes the evidence we have—which is necessarily incomplete—and makes decisions about what we as a nation should do based on that evidence. Those “shoulds” are opinions, so they’re ripe for argument. In that sense, politics is a layer on top of the science.

How the Guidelines are Written

The process looks something like this: a Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee reviews thousands of published, peer-reviewed studies, and puts together a report about their findings. Then the United States Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services jointly issue the dietary guidelines based on that report. Lobbying, actions of Congress, and comments from the food industry and medical and health associations shape those final guidelines. If a rule will promote health but hurt an industry’s bottom line, it might not make it into the final guidelines—at least not without a fight.

As we reported earlier, a surprising number of experts agreed that the 2015 committee report started with a reasonably accurate take on the best available dietary science. Still, you can’t please everybody all of the time, and the finished guidelines have some glaring differences from that report. Here are the major newsworthy recommendations and the controversies surrounding them.

Sugar

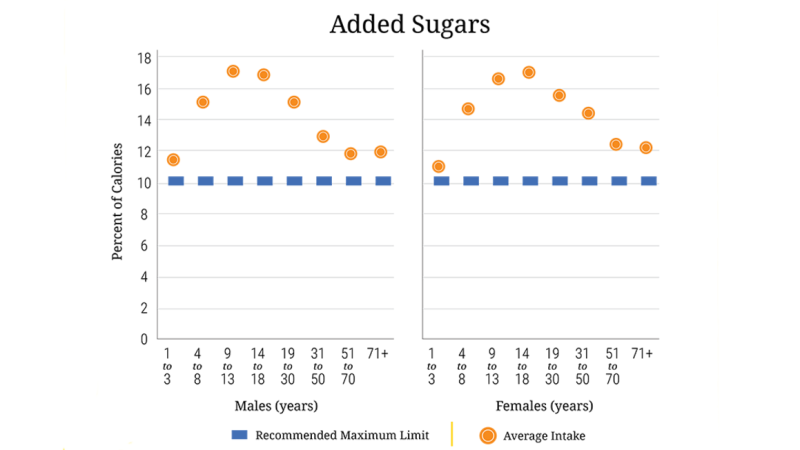

What the Guidelines Say: “Consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from added sugars.”

What changed: This is brand new: the previous guidelines didn’t set a cap on added sugars. Instead, they said that people should reduce their intake of certain fats and added sugars, and that an appropriate amount of those two items together would be somewhere around 5% to 15% of total calories.

There were some changes from the 2015 scientific report, too. Fruit juice concentrates were quietly dropped from the advisory committee’s definition of added sugars (they’re a commonly used sweetener in “natural” foods).

The finished guidelines also toned down language about cutting out soda and other sugary beverages, instead saying that people should limit sugar itself. Currently, the average American gets 13% of their calories from added sugars, with half of that from beverages. This varies by age, as the graph above shows. A single can of Coca-Cola is enough to put you over the daily limit (11.5% on a 2000-calorie diet).

Who’s saying what: Almost everyone agrees we need to eat less sugar, so this rule was widely applauded. The World Health Organization also recommends a 10 percent limit (noting that 5% would be even better), but they include both natural and added sugars in that total. Compared to WHO guidelines, then, the US guidelines are weaker.

The sugar rule is hard to follow without a clear way to find out how much added sugar is in a food. The US Food and Drug Administration, which governs food labels, has proposed listing added sugars. Makers of processed foods have been fighting that idea.

Predictably, makers of artificial sweeteners are happy about the new rule, while the Sugar Association issued a statement griping that the new guidelines aren’t based on completely solid science with “proof of cause and effect.” That’s because nutrition science never has that level of certainty. The idea of restricting sugar is as close as we get to an all-around win.

Even those who love the new rule can still find room to be critical of how the guideline is described. Marion Nestle, analyst and author of Food Politics, feels that the guidelines didn’t get specific enough about sugary drinks. She writes:

[T]hese Dietary Guidelines, like all previous versions, recommendfoods when they suggest “eat more.” But they switch to nutrientswhenever they suggest “eat less.”

In the 2015 Dietary Guidelines,

- Saturated fat is a euphemism for meat.

- Added sugars is a euphemism for sodas and other sugar-sweetened beverages.

- Sodium is a euphemism for processed foods and junk foods.

Chalk that up to politics: food makers want you to eat more of their foods, so you’ll rarely see a government document saying to eat less. (Nestle described the workings of this unofficial policy in detail in her book.) Instead, the guidelines either say to restrict a nutrient, like sugar, or to “choose” a different food, like swapping water for soda.

The bottom line: You already know. Eat less sugar, drink less soda.

Meat

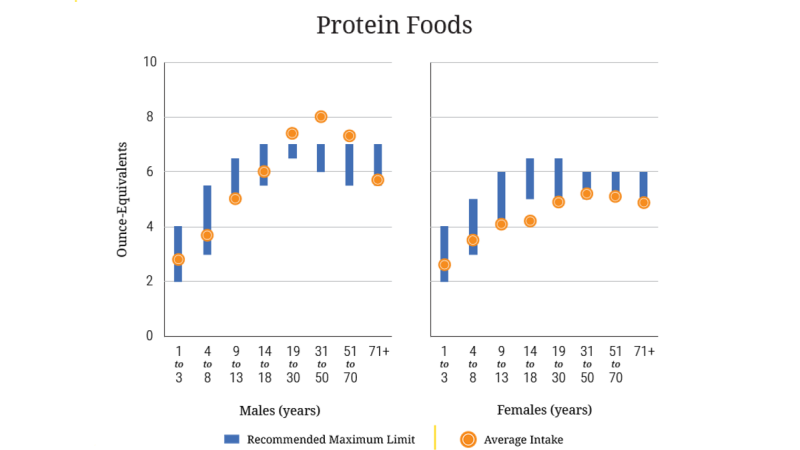

What the guidelines say: A “healthy eating pattern includes…a variety of protein foods, including… lean meats” but limits saturated fats. Except for teen boys and men, nobody is directly told to eat less meat.

What changed: A restriction on meat, included in the scientific report, was dropped from the final guidelines. The committee made the landmark decision to include sustainability as a factor in the guidelines, and recommended reducing meat in part because of its impact on the environment. The finished guidelines have no mention of this. Politicocredits the changes to “furious lobbying” by the meat industry.

Who’s saying what: On the surface, this one has broad support: the watchdog group Center for Science in the Public Interest, which tends to favor low-fat and vegetarian diets, reads between the lines to applaud“the overall advice on eating less meat.” The meat industry reads it the opposite way, as endorsing meat. (Marion Nestle says meat producers “should be breaking out the champagne.”) The Ohio Country Journal writes:

The bottom line according to [the National Pork Producers Council] is that meat remains an important part of the American diet. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans do not contain any provisions that should drive federal, institutional or consumer shifts away from meat as the major protein source in diets, and they do not include extraneous matters, such as requiring food producers to meet sustainability standards or taxing certain foods as a way to reduce their consumption.

Sustainability was a hot-button issue in the guidelines’ development. Congress tried to quash mention of sustainability with a directive issued in 2014, before the advisory committee even made their report, which said that the guidelines must stick purely to nutrition. The USDA and HHS secretaries agreed to drop the issue.

It’s hard to justify keeping sustainability out of the guidelines when economic concerns are obviously at work in their construction, and the USDA is tasked with promoting both. After all, the guidelines have a major effect on what foods Americans grow and buy, which in turn affects the economy and the environment. Dr. David Katz of Yale’s Prevention Research Center, who calls the finished guidelines a “national embarrassment,” noted the “hypocrisy” in including exercise in the guidelines while eschewing sustainability—after all, exercise isn’t purely nutrition either.

Groups like the American Cancer Society objected to the lack of a meat limit for another reason: the connection between red meat and cancer. The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer ruled that red and processed meat “probably” cause colorectal cancer. That designation is less certain than it sounds, but concerns about a link between cancer and red or processed meats have been around for a while. The dietary guidelines are silent on this issue.

The bottom line: Meat is harder on the environment than most plant foods; red and processed meat are maybe linked to cancer. We’d understand if you decide to err on the side of caution and eat less of it.

Fat

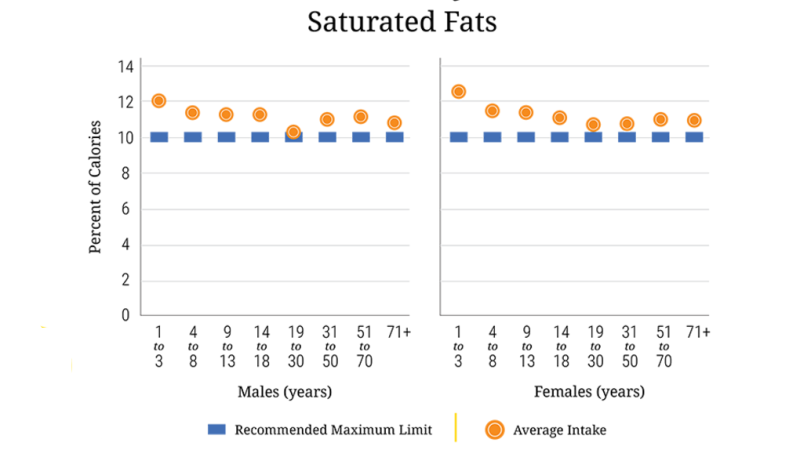

What the guidelines say: “Intake of saturated fats should be limited to less than 10 percent of calories per day by replacing them with unsaturated fats.”Unsaturated (“good”) fats are still okay, and trans fats should be “as low as possible.” Total fat should be 25-35% of calories for most adults.

What changed: The 10% limit on saturated fat is new, and it’s unchanged from the advisory committee’s report. Total fat has changed slightly, from a range of 20-35%. The dietary guidelines have always been harsh on fats and especially saturated fat, and that’s still the case here.

Who’s saying what: The Washington Post called the decision to stick with a saturated fat limit the guidelines’ “most controversial move.” Saturated fat has been vilified for decades, but a growing faction of scientists now say this was a mistake. We’ve covered that idea here: multiple studies show that saturated fat may not be bad for your heart after all.

But not everybody buys that theory. The American Heart Association still warns people away from saturated fat, criticizing the studies that say saturated fat is okay. They recommend an even lower intake, with saturated fat making up 5-6% of calories.

Both camps, and the dietary guidelines, agree that monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats are still good for you. These are the fats found in plant foods like nuts and avocados. They don’t recommend replacing saturated fat with carbohydrate calories, since that also raises your heart disease risk. And everybody still hates trans fats.

The bottom line: Good fats are good, trans fats are bad, but saturated is a toss-up. The pendulum of scientific truth seems to be swinging towards the “saturated fat is okay” camp, but it’s too early to say for sure. Your call.

Cholesterol

What the guidelines say: “Individuals should eat as little dietary cholesterol as possible while consuming a healthy eating pattern.”

What changed: Previous years’ guidelines had put a 300-milligram limit on cholesterol. The 2015 advisory committee dropped the idea of limiting cholesterol entirely, writing that “Cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.” The finished guidelines brought back the idea of reducing cholesterol, but left off any specific number.

Who’s saying what: The Physicians’ Committee for Responsible Medicine threatened to sue the USDA and HHS, saying that the cholesterol warnings were the result of illegal influence from the egg industry.

But the lack of a cholesterol cap brings the US recommendation in line with those from other countries, and with what we’ve known for a long time: that cholesterol in food has little to no effect on the cholesterol in your bloodstream, which does matter.

The bottom line: Go ahead and eat those eggs.

Other Noteworthy Recommendations

The rest of the guidelines are less controversial. Here’s a rundown:

- Sodium still has a limit of 2,300 milligrams (the average American gets 3,400).

- Alcohol is okayed at one drink a day for women, two for men, and zero if you don’t normally drink (in other words, don’t start.) There’s a handy chart on how to count drinks. For instance, a 12 ounce beer is one drink if it’s 5% alcohol.

- Caffeine appears in the guidelines for the first time. Up to 400 milligrams “can be incorporated into healthy eating patterns,” but again, no need to start drinking it if you don’t already. The guidelines budget you five 8-ounce cups of ordinary coffee, or one Starbucks Venti.

- Fruit and Vegetable amounts are unchanged (2 cups of fruit, 2.5 cups of vegetables) and you’re still supposed to eat your colors—in other words, consume red and orange vegetables, yellow ones, and dark green leafies. Each group has a different profile of vitamins and other nutrients.

- Grains also hold steady at 6 ounces per day, and at least half of that should be whole grains. The new guidelines include mediterranean and vegetarian diets with slightly different amounts of each food group than the standard “Healthy US-style,” so check those out if you’re the type to weigh your grains to the half-ounce.

Most of the guidelines haven’t changed too much since they were last released in 2010, but some of the details represent an evolving understanding of what our bodies do with food. Food marketers arealready planning how they’ll take advantage of the new guidelines, withMcCormick sending out press releases about using their spices in place of salt. A spokesperson for a PR firm that represents several processed food companies described the recommendations as saying “There’s no bad foods, just bad portions.” In other words, it’s business as usual in the food industry—but now we have just a little more information.

Source(s):