National Geographic Connects to an ‘Inner Yellowstone’ Natives Always Knew About

Time seems to move slowly at Yellowstone National Park, a 3,500-square-mile wilderness known for its putrid hotspots, hellish geysers, petrified trees, stunning vistas and untamed animals.

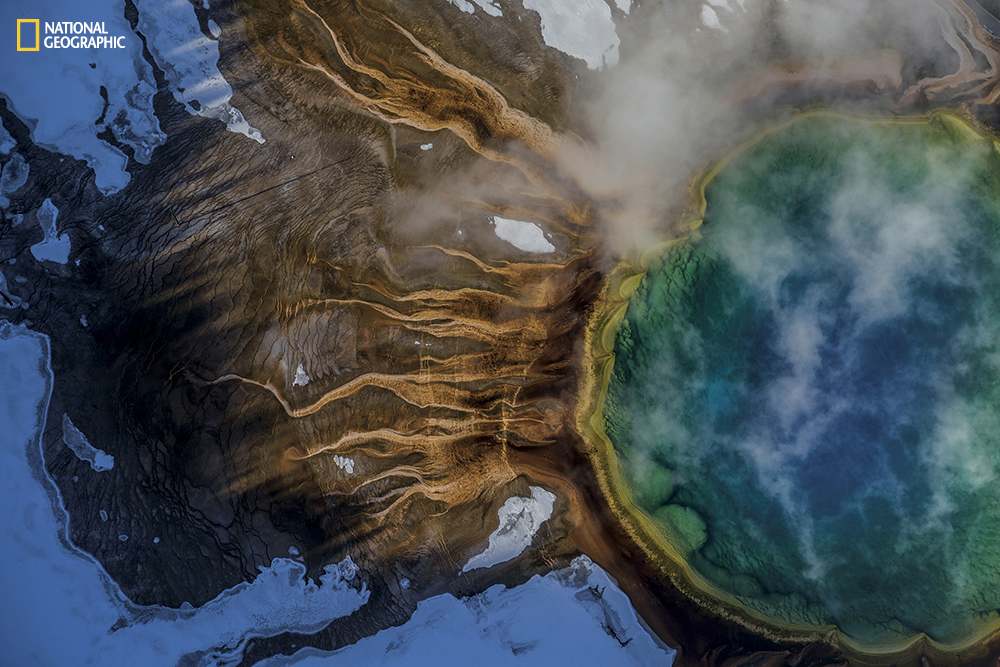

This park, which spans parts of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho, boasts millions of years of geologic history. Rivers slice through solid rock, revealing vividly colored canyon walls; geysers spray pungent, boiling water hundreds of feet into the air; mud pots gurgle and, despite its 4 million visitors per year, much of the park remains untouched by humans.

But Yellowstone also is a place of constant transition, according to David Quammen, of National Geographic magazine.

“It’s more than just a park,” writes Quammen, of Bozeman, Montana. “It’s a place where, more than 140 years ago, people began to negotiate a peace treaty with the wild. That negotiation continues today, with growing urgency, at Yellowstone and all over the planet, as the human world expands and the natural world retreats.”

Established by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1872 “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” Yellowstone is the world’s first national park, representing the intersection of wilderness and government protection. It also is the subject of an entire magazine published in May by National Geographic.

The issue, titled “Yellowstone: The Battle for the American West,” is part of a yearlong celebration of national parks commemorating the centennial anniversary of the National Park Service. National Geographic sent one writer and six photographers to Yellowstone, where they worked full-time for a year, Deputy Editor Jamie Shreve said.

The result was 170 pages of photos and a 15,000-word “mega-story” detailing the geothermal history of Yellowstone, its wildlife and ecosystem, attempts to preserve the park and a look at the area’s 11,000-year human history. The “human element” of the story is inextricably tied to the wildlife, Shreve said, and it begins long before white settlers “discovered” the park in the late 19th century.

“The notion it was founded under was the ‘benefit and enjoyment of the people,’” he said. “That’s not inclusive. They were talking about white people, not the Native population of the Yellowstone ecosystem at the time.”

Although Yellowstone—and national parks in general—are now celebrated for their preservation of scenery and wildlife, that wasn’t always the case. Shortly after it was established, Yellowstone became a “disaster zone, neglected and abused, for more than a decade,” Quammen writes. “At the outset, the park was an orphan idea with no clarity of purpose, no staff, no budget.”

The park’s first superintendent visited Yellowstone only two or three times in five years. Meanwhile, hunters helped themselves to the wildlife, killing elk, bison and bighorn sheep in “industrial quantities.” By one account, a pair of brothers shot 2,000 elk near Mammoth Hot Springs in 1875, taking only the tongue and hide from each animal—part of what historians call the “massive slaughter” at Yellowstone.

By 1886, the U.S. Army took over the park, changing the way the government related to wilderness. Another change took place in the 1880s when Gen. Philip Sheridan, the man most famously remembered as commander of the campaigns against the Plains Indians and advocate of exterminating the bison as a way of crushing tribal culture, visited Yellowstone in 1882.

The visit changed Sheridan’s view of bison, Quammen writes. After seeing the commercial slaughter, vandalism and killing of wildlife “for the hell of it,” Sheridan offered troops to protect the park.

Yet poaching continued into the early 20th century. By 1901, only a few hundred bison remained in America, including about two dozen in Yellowstone. Park officials managed to breed them, saving the bison population from extinction. Then, in August 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed an act creating the National Park Service, an agency under the Interior Department charged with protecting all national parks and monuments.

No population was more devastated by the bison slaughter than the Natives, said Leo Teton, a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. Teton, 59, was interviewed and photographed for the magazine.

“We’ve been in that part of the country for eons,” he told ICTMN. “Back in the day, that was our aboriginal hunting grounds. Back in the day, we hunted for subsistence.”

But the Native connection to Yellowstone runs much deeper than hunting, Teton said. Long before explorer Ferdinand Hayden regaled Congress with tales of “peculiar vividness” and “remarkable prismatic springs,” Natives regarded the area as sacred.

“We called it the healing waters,” Teton said. “That’s where we went and prayed, cleansed ourselves. We used it as a place to meet, to mingle, to hunt and trade.”

Much has changed at Yellowstone since it became a national park, and its human relationship is more complicated than ever before, Teton said. Tribes continue to hunt bison in limited quantities near Yellowstone, using the animals for meat and ceremonial items, yet they also contend with naïve or uninformed visitors—like the tourists who put a baby bison in the trunk of their car because they thought it looked cold.

RELATED: Tourists’ Attempt to ‘Save’ Yellowstone Bison Calf Results in its Death

“We still say establishing a park there was a good thing because it preserves the land,” Teton said. “But now our sacred place is off limits to us, and Yellowstone is full of tourists. Tourists who approach buffalo because they think they’re cute, or because they want them as pets, or because they think they need to be rescued.”

National Geographic is exploring these complex relationships among humans, wildlife and the land itself in its “Power of the Parks” series, which runs through December. The series also goes way beyond the boundaries of the United States, with topics that include coral reefs in Cuba, Seychelles Island off the coast of Madagascar and Manú National Park in Peru—home to uncontacted indigenous people. The series will end with stories examining climate change and the next generation of park visitors.

“These are not static entities, but living landscapes that people really care about,” Shreve said. “Yellowstone is now thriving, and there’s a sense of vibrant habitat there that people really enjoy knowing is there even if they’re not there. If we’ve used this issue to help people connect to that inner Yellowstone that’s in all of us, we’ve done our job.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/06/08/national-geographic-connects-inner-yellowstone-natives-always-knew-about-164680