Native History: The Famous Modoc Brave Who Wasn’t

With the American public eager to see what the disastrous Modoc War of 1872–1873 looked like, rising-star photographer Edward Muybridge knew what he needed to do: Give his viewers what they expected to see. And if that meant creating fiction, he was willing to play.

An English immigrant who settled in San Francisco as a seller of fine books and engravings, Muybridge ventured into photography after a stagecoach accident left him brain-damaged. The injury eroded his social skills and led to outbursts of murderous anger—Muybridge would later kill his wife’s lover and be acquitted of murder by a jury of married men—but it also unlocked his creativity in ways that made him an inventive genius.

To feed the market demand for artistic landscapes and Native nostalgia, Muybridge traveled the West to shoot the country and its fast-vanishing Indigenous Peoples. He also photographed military facilities in the Bay Area on commission from the Army. This experience led the United States government to dispatch Muybridge to the Lava Beds to photograph the Modoc War for archival purposes.

Besides shooting the immense, fierce, volcanic landscape, Muybridge captured combatants on his glass negatives. He took group portraits of senior officers, Indian women working for the Army, translators Frank and Toby Riddle, and Donald McKay and his company of 72 Native scouts from the Warm Springs Reservation in north-central Oregon.

Photographing the Modoc War presented a grueling challenge. Cameras of the 1870s used glass negatives that made them heavy and cumbersome. Instead of the massive view camera that had served him well for landscapes, Muybridge opted for a more compact and portable stereo camera that took two images of the same object from slightly different angles to deliver a more-than-3D version of reality. Still, even the stereo camera was heavy and hard to handle.

The war made the task no easier. In the two weeks before Muybridge arrived, the Modocs had been driven from their Lava Beds stronghold and were on the run. The fast-moving skirmishes far from base camp that had become the new normal offered no opportunity to photograph actual fighting. The enterprising Muybridge needed another way to get what he was after.

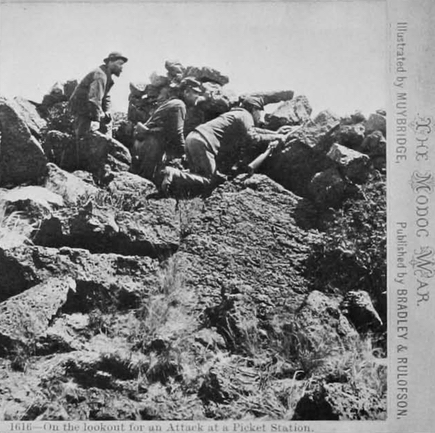

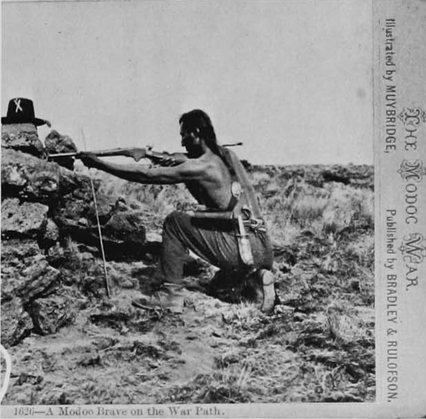

Muybridge sought more than set-pieces; he wanted action. So he had three infantrymen creep on hands and knees behind a tumble of boulders and peep over a ridge top, as if tensely alert to enemy sharpshooters. In fact, the closest hostile Indian was miles away. Seeking an image of a Modoc fighter and figuring that one Native looked pretty much like any other, Muybridge posed Warm Springs scout Loa-kum Ar-nuk. The photographer put the scout down sighting a Spencer carbine steadied by a shooting stick. The image from the left shows the scout’s knife hanging from his belt, a blend of the traditional with the civilized new of the repeating rifle. The image from the right emphasizes Loa-kum Ar-nuk’s low stance behind a rock wall and his thousand-yard stare. Transformed into a woodcut, this second image of the scout was published in the June 21, 1873, Harper’s Weekly over the caption “Modoc brave lying in wait for a shot.”

Later that year, a leading San Francisco photographic studio released a sales catalogue of Muybridge’s Modoc War photographs. Loa-kum Ar-nuk appears again, from both sides, with the caption reading “A Modoc Brave on the War Path” on each.

It was bad enough that Muybridge used a deceptive fiction to spice his product and boost sales. It was even worse when one considers who the Warm Springs scouts were—desperately poor Native men from a hardscrabble reservation who signed on as trackers and shock troops for three hots and a cot. Turning a poorly used scout in the Army’s employ into a hostile Modoc for the purpose of selling magazines and photographs was a self-interested fraud.

Not that the deception affected Muybridge’s career. He went on to take stunning photographs of San Francisco and Central America; he developed a way to photograph bodies in motion that laid the foundation for the modern film industry; and he hobnobbed with railroad magnate Leland Stanford and fellow inventor Thomas Edison.

As for Loa-kum Ar-nuk, he had returned to the hard reality of Warm Springs by the time Harper’s Weekly carried his fictionalized image. Likely he never learned of his few seconds of anonymous fame as the Modoc he wasn’t.

Robert Aquinas McNally is a writer and poet working on a narrative nonfiction book entitled “The Modoc War: Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age,” from which this article is adapted. Find out more about his work online.

For further reading:

Ball, Edward. The Inventor and the Tycoon: A Gilded Age Murder and the Birth of Moving Pictures. New York: Doubleday, 2013.

Palmquist, Peter. “Image Makers of the Modoc War: Louis Heller and Eadweard Muybridge.” The Journal of California Anthropology, vol. 42, no. 2 (1977), pp. 206–241.

Riddle, Jeff C. The Indian History of the Modoc War. Eugene, Oregon: Urion Press, 1974; originally published in 1914.

Solnit, Rebecca, River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West. New York: Penguin Books, 2003.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/06/21/native-history-famous-modoc-brave-who-wasnt-164623