Lillian Pitt: The River People Are Still Here, Still Creating

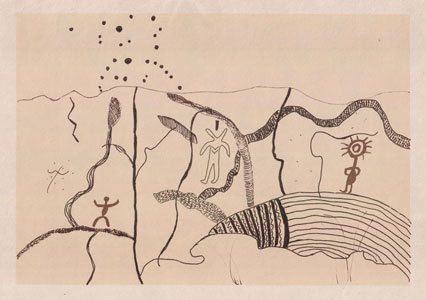

Artist Lillian Pitt, Wasco/WarmSprings/Yakama, has been internationally known for her ceramic masks, cast-glass sculpture, sterling silver jewelry, and prints for over 30 years. Much of her work is inspired by the rock carvings and rock paintings of her Columbia River ancestors.

She has collaborated with Vietnam Memorial artist Maya Lin. Her work has been exhibited in more than seven countries and is held in several important collections, including those of the National Museum of the American Indian, the Burke Museum, and the Heard Museum.

Now in her 70s, Pitt continues to explore new ways of presenting her culture to the world – drypoint etchings, linocuts, lithographs and monoprints. An exhibit of her prints opened at Jeffrey Moose Gallery in Seattle on February 16 and continues through May 7.

In this interview, Pitt talks with humility and humor about her continued growth as an artist – and what she hopes people take away from her work.

Your latest works at Jeffrey Moose Gallery – can you tell me how these pieces came about?

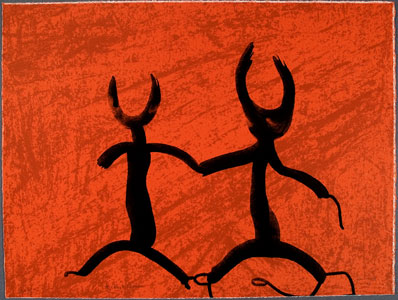

They’re inspired by the petroglyphs from the Columbia River Gorge. Almost everything I do is related to my Ancestors in the Gorge. So, titling them – I just thought I would give them the names of our dances in the longhouse, which is the Round Dance, the Rabbit Dance and the Owl Dance.

These are lithographs and they were printed by Frank Janzen at Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts in Pendleton, Oregon. I kind of enjoyed that because it was my first time doing something that was done with a brush. I painted the original image with tusche ink, which is a special ink that you paint on zinc, on metal. It’s a printing process, a lithography process, so you only have one chance to make your image. You can’t redo it. So it was an amazing experience to do that for the first time.

As an artist, was it hard to do that and just have to be satisfied with your work?

I had practiced doing the drawing on a piece of paper, and I had not anticipated the dripping [process] and so that part was really a wonderful surprise (laughs). And I thought, well, that looks good. And so, you know, it’s amazing when you’re creating, your expectations aren’t as preordained, you know?

It amazes me, the breadth of work you’ve done – from raku to cast glass masks to jewelry and printmaking. It seems like you continue to explore as an artist.

Oh, yeah, it’s a lot of fun. My friends have been so helpful. They come up with all these bright ideas – “Have you tried this and have you tried that?” And I said, “No.” “Well, then let’s do it.” And so I just say “OK.” I trust my friend’s works. They’ve been my best critics and my best helpers and my best teachers and mentors.

With any of your work, are you able to work outside at all?

When it’s too big, I have to work outside. I’m also doing a show at Clatsop Community College in Astoria, Oregon, “Out of the Box," a metaphor for doing something different. So I have a big tripod that I’m going to use. I’ve woven some sticks together, like the River People wove their mats to put out on their houses and they would overlay them and it was good insulator for them. And they would use [mats] for their tablecloths; when we would eat they would put the food on them. They used the tule for that, whereas I just use sticks, and so what I’ll do is I’ll put that in the apex of my tripod. I am thinking of breaking it apart and using it as a broken-down house that was in the “Saving our Sacred Land” DVD project, four DVDs on saving our sacred land. The Chinese just mowed down the indigenous Balinese families’ houses so they would not be a bother to them … I wove a small piece to hold the cover of the four DVDs and put them on a tripod, representing the Hawaiians’ efforts to clean up their island after it was bombed over and over [during World War II]. The broken box will go on the floor. Some ideas come out more easily in my head than in reality. So, we will see.

So, I’m doing two or three different things at once. I’m looking at the box, thinking how should I break it, does it need to be painted some more. And so I’m thinking about that and looking up at the rafters wondering which sticks to use. I’m just kind of a chaotic-type person and I really try not to be but it’s who I am.

How long have you been an artist?

I started out 34 years ago, and my work that started me was when [Navajo gallery owner] R.C. Gorman came to town. I had only done five pieces that were raku fired. I had terrible pictures of them and I took them to his opening and showed him the pictures and he was my first buyer.

Who do you continue to learn from and draw inspiration from as an artist?

[Wiyot artist] Rick Bartow has been a dearest friend and his work continues to grow and to baffle me and leave me in a quandary and I get amazed at what he can do. And [Mi’kmaq artist] Gail Trembley and [Colville printmaker] Joe Fedderson and Joe Cantrell with his wonderful photography. We’ve all been a tight-knit group. And now [Mexican painter] Analee Fuentes has been there for me; we make prints together, we went to New Zealand together. Richard Nolan, art teacher at Clatsop Community College, is Hawaiian and we’ve been to New Zealand together and worked in clay. I’ve gone to work with prints with Analee in New Zealand and [Maori master printer] Gabrielle Belz in New Zealand. People from all over have been so helpful and so inspirational to me.

You and other indigenous artists from the U.S. and Canada traveled in 2015 to New Zealand to work with Belz. What did you find you all have in common as indigenous artists and indigenous people?

What we have in common is a strong sense of identity, of our culture, and of our place on the planet and our strong ties to our ancestors. So it makes everything much more precious.

What medium do you enjoy working with the most?

Clay.

Do you ever get a chance to just watch someone looking at your art and they don’t know you’re there, and you just watch and see what their reaction is?

(Laughs) It’s really fun. But I sometimes get too shy to say, “I did that,” in case they didn’t like it.

I doubt you get that very often. A final question: When people see your art, what do you hope they take away from it?

I would want them to know that all the River People are still here. After 12,000 to 18,000 years, we are still here, still creating, and here’s one person who knows exactly who she is.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/03/12/lillian-pitt-river-people-are-still-here-still-creating-163737