Largest-ever Gulf of Mexico dead zone

For 32 years, scientists have tracked the oxygen-depleted waters that appear each summer in the Gulf of Mexico. This year’s dead zone is the biggest yet.

An old 1985 photograph of freshwater from the Mississippi River flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. Image via NASA.

Scientists have been tracking the oxygen depleted waters that appear each summer in the northern Gulf of Mexico for 32 years now. Known as the “dead zone” because most marine life cannot survive under such harsh conditions, this year’s extent of hypoxic (i.e., deficient in oxygen) waters has grown to 8,776 square miles (22,730 square kilometers) as of July 2017 — it’s the largest dead zone ever recorded in this region, which has some people wondering what more can be done to fix this problem.

Nancy Rabalais, a research professor at Louisiana State University who led the July 24–30 survey of the dead zone onboard the R/V Pelican, stated:

We expected one of the largest zones ever recorded because the Mississippi River discharge levels, and the May data indicated a high delivery of nutrients during this critical month which stimulates the mid-summer dead zone.

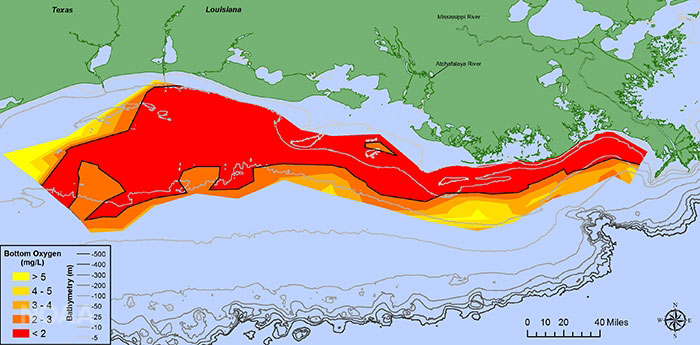

The extent of the Gulf of Mexico dead zone in 2017 was the largest ever recorded. Image via Nancy Rabalais, Louisiana State University.

Nutrients including nitrogen and phosphorous released into the Mississippi River watershed from sources such as farmland, fertilized lawns, and sewage treatment facilities can trigger algal blooms once they reach the warm, slow moving waters of the Gulf of Mexico. As the plentiful algal cells begin to die-off and decompose, this stimulates the growth and respiration of microorganisms, which use up most of the oxygen in the water. The low levels harm marine life such as fish and shellfish that need oxygen to survive. Years with heavy spring rains, such as 2017, typically lead to larger dead zones because more nutrients get flushed into the marine ecosystem than in dry years.

Signs of the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico first appeared in the 1970s, and while year to year fluctuations occur because of droughts and hurricanes, the dead zone has generally increased in size over the past several decades. It is now one of the largest of its kind around the world. For the past five years, the dead zone has averaged 15,038 square kilometers (5806 square miles), which is three times higher than the conservation goal of 5000 square kilometers set by the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force.

Changes in size of the Gulf of Mexico dead zone since monitoring began in 1985. The dead zone is an area of very low dissolved oxygen (D.O.) that is harmful to fish and shellfish. Image via Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON).

Reducing nutrient runoff from the Mississippi River watershed is key to reducing the size of the Gulf of Mexico dead zone, according to the task force. An interim goal has been set to reduce nutrient runoff by 20% in 2025, and further reductions will be attempted thereafter. The size of the dead zone is not expected to reach the target area of 5000 square kilometers until 2035.

As for the actual implementation of nutrient reduction measures, that work is being done at the state and local levels. So far these measures have included activities such restoring wetlands that can trap nutrients, reducing the amount of fertilizers applied to agriculture fields, planting buffer strips and retention ponds around areas with high rates of runoff, and fixing leaking septic tanks. A good article on the benefits of using cover crops was just published in Mother Jones, and the Nature Conservancy also has many good articles on techniques that are effective in reducing nutrient runoff. The challenge going forward will be to figure out which techniques work best and how to pay for them.

Bottom line: The recurring summer dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico has reached the largest size ever recorded, as of July 2017. The appearance of the dead zone is tied to nutrient-rich runoff from the Mississippi River basin, and heavy spring rains in 2017 likely contributed to its growth this summer.

Deanna Conners is an Environmental Scientist who holds a Ph.D. in Toxicology and an M.S. in Environmental Studies.

© 2017 EarthSky Communications Inc.

http://earthsky.org/earth/largest-ever-gulf-of-mexico-dead-zone