February 2016 marked the 160th anniversary of the death of Benjamin Wright, whose bloody career as an Indian killer makes all too clear the dark reality of America’s genocide.

Wright had an unlikely beginning for an Indian killer: he was born and raised Quaker in Indiana. As a teenager he left that life behind and drifted west to Kansas. There the 20-year-old, an avid hunter and tracker, joined a wagon train for Oregon in 1847.

On the way west, the story goes, Wright fell for a pretty young thing who was later killed in an Indian raid, and he vowed life-long retribution against all Indians. This event—a common 19th century literary trope—likely never happened. But it did happen that, soon after reaching Oregon, Wright enlisted in a militia to put down the Cayuse Nation. In this dirty work of hunting and killing Indians he found his calling.

After discharge, Wright crossed into California and settled along Cottonwood Creek, some 20 miles north of rough-and-ready Yreka. He made his living by killing Indians for bounty. Remarkably, Wright affected the fashion of the people he hunted: wearing buckskins, growing long hair, and shaving clean but for a soul patch. He looked so much like an Indian that, in a night skirmish, another vigilante nearly knifed him. Even after that near-death experience, he kept his hair long.

Wright had a fondness for trophies: scalps, fingers, ears and noses, often sliced off while their owners were still alive. He kept Indian women as sexual slaves, killing any man who objected. And when he drank, this mean man turned even meaner.

Wright’s best opportunity to kill Indians lay to the east, in the Modoc homeland around Lower Klamath, Tule and Goose lakes along the recently charted Applegate Trail. More and more emigrants were following it to the gold fields of southern Oregon and northern California. All these people and their wagons and livestock, tromped through the Modocs’ homeland, grazing grass to the roots, burning firewood, shooting game, fouling water, spreading disease.

At first, though, emigrants passed without incident. Then some Modocs fought back, attacking wagon trains along the Tule Lake shoreline. Tall tales of Modoc atrocities inflated with impossible death tolls and lurid fictions of torture and rape spread from settlement to settlement.

Yreka’s miners raised a militia of 65 men, Ben Wright among them, and headed east to teach the Indians a lesson. They found no one to fight until, on the way home, they were hit in a nighttime attack, possibly by Indians from the Pit River country, that left several wounded. After that, the militiamen wanted revenge.

They got it the next morning when they came across 14 Modocs in a summer camp cooking breakfast. The Natives offered no threat, but almost all were shot down and scalped. Pushing on, the militiamen encountered another group of peaceful Modocs, who approached to ask for bread, bacon, and coffee. The whites killed them and took their scalps for display back in Yreka.

State policy sanctioned and funded such death-squad raids. Peter Burnett, California’s first civilian governor, had declared that “a war of extermination will continue… to be waged until the Indian race becomes extinct,” and the state legislature appropriated a half-million dollars to pay for militia campaigns like the raid against the Modocs.

Counting his money back in Yreka, Wright decided the year remained young enough to kill more Indians. He formed a follow-up militia of 20 men and returned to Modoc country.

The Indian killer and his vigilantes rode past the principal Lost River village under the eyes of the Modocs, who displayed no hostility despite the earlier raid, then camped well downstream. Under cover of darkness, Wright’s men crept close and, as the sun rose, opened fire. The Indians, armed with bows and arrows, could only flee. More than a dozen were killed. Next, Wright and his men fell upon an island village where Lost River flowed into Tule Lake and slaughtered 15 more.

Survivors from the two attacks took shelter in a large cave on the far side of Tule Lake. Wright and his posse, who had run out of food, piled fuel at the cave’s mouth and set it afire. The blaze was still burning 24 hours later, and a hungry Wright decided the Indians inside had to be cooked or smothered. He and his men rode back to Yreka, drawn by warm beds, hot meals, and willing women. They did not know that the Modocs survived the cave fire and realized they were slated for extermination.

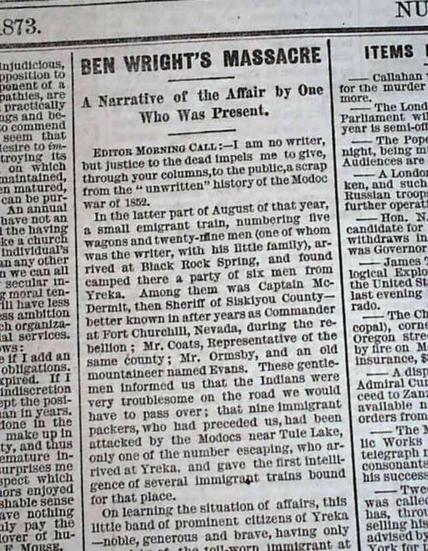

Wikipedia

“The Modoc War—Soldiers Recovering the Bodies of the Slain,” a wood engraving published in Harper’s Weekly, May 3, 1873.

The following summer, Wright returned to his mission in the Tule Lake country at the head of another militia. As soon as he and his men arrived, they attacked a group of Modocs—supposedly besieging a wagon train—and killed 30 to 35 Indians without losing a man.

The vigilantes spent the next three months escorting wagon trains from Clear Lake to Upper Klamath Lake. This duty gave Wright occasional opportunity to kill. When he and some of his men spotted two Indian women running for shelter, the mounted whites rode the pair down. One woman died outright from gunfire. The other suffered only an arm wound unlikely to kill. Wright dismounted and knifed her. Screaming, she bled out at the former Quaker’s feet.

Wanting something grander than a single knifing, the Indian killer hoisted a white flag and sent word that he sought to negotiate peace. A large group of Modocs camped nearby to talk. All remained peaceful until dawn on the sixth day. Sending his men to encircle the camp, Wright holstered two revolvers under his serape and strode in among the sleeping Modocs. When he came to their leader, the Indian killer shot the man down then zigzagged through the stunned Indians, shooting as he ran. His men poured in rifle rounds all the while. Caught flat-footed, armed only with bows and arrows, Modocs fell one after another, women as well as men. Just a handful escaped the killing field.

Not a single white died in what became known as the Ben Wright Massacre. The number of Indian dead is variously given as between 30 and 90, with the most likely total around 50. To a small nation like the Modocs, the toll was devastating.

RELATED: Fight the Power! 100 Heroes of Native Resistance, Part 2

The Indian killer and his men again lifted scalps for display back in Yreka, where the townspeople threw a party in their honor. And the vigilantes made major money from the massacre. The California legislature paid privates $4 a day for their service, about eight times the per-diem rate of a regular-army soldier. The Indian killer himself drew $744, almost $21,000 in today’s currency.

His success against the Modocs won Wright appointment as Indian agent along Oregon’s southern coast. There he met a poetically just comeuppance.

The story opens in the muddy main street of Port Orford. A drunken Wright assaulted Chetcoe Jennie, the government interpreter who was his mistress of the moment, stripped her naked, and whipped her through the rain-soaked town. Set on avenging this ignominy, Jennie threw in with a group of Indians pushing back against the rising American tide. The leader was Enos, a Shoshone guide and scout who had worked for Wright and, for reasons that remain hidden, was as motivated by revenge as Chetcoe Jenny. Perhaps after a dance that turned into a brawl, perhaps in a dawn ambush, the reckoning came in the early hours of February 23, 1856, close to the mouth of the Rogue River. Enos killed Wright with an axe and—as legend has it—ate the dead man’s heart raw, sharing the meal with Chetcoe Jennie.

Less than two months later, Enos was strangled in a lynch party’s noose. The avenged Chetcoe Jennie vanished into the forest, never to be seen again.

Yet, heartless as he was, Ben Wright had the last laugh. For all the blood that clung to his hands, his countrymen considered him a hero. Historian and novelist Frances Fuller Victor, as the most literary example, published an apologia entitled “A Knight of the Frontier.” Without the least irony, Fuller named Wright one “who, so far as we know always labored in the cause of humanity.”

Proclaiming a racist sexual predator and Indian killer chivalrous not only turns sin into sainthood; it also exposes the deep-seated mythic belief that drove America’s westward expansion. Emigrants saw the motives behind their extermination and dispossession of Indians as both blameless and divinely blessed. This imagined innocence painted every action by emigrants, including murder and rape, in a bright light and made Indian resistance inherently infernal. Tales of massacre, torture, and rape nurtured a twisted outrage that allowed settlers to cloak themselves in innocence even as they destroyed Indians.

Such is America’s original sin: the righteous genocide that made Indian killer and rapist Ben Wright a “knight of the frontier.”

Robert Aquinas McNally is a writer and poet at work on a narrative nonfiction book about the Modoc War of 1872–1873 entitled “The Stronghold: The Biggest Indian War You Never Heard of,” from which this article is adapted. Find out more about his work at ramcnally.com.

For further reading:

Bancroft, Hubert Hugh. History of Oregon. Volume 2. San Francisco: The History Company, Publishers, 1888.

Burnett, Peter. “The Governor’s Message.” Sacramento Transcript, January 10, 1851.

Clark, R.A. “Ben Wright’s Treachery.” Letter to the San Francisco Chronicle, May 6, 1873.

Fisher Don C. “Ben Wright,” (typescript, Lava Beds National Monument, 1940).

James, Cheewa. Modoc: The Tribe That Wouldn’t Die. Happy Camp, CA: Naturegraph Publishers, 2008.

Lindsay, Brendan C. Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide, 1846–1873. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

Madley, Benjamin. “California and Oregon’s Modoc Indians: How Indigenous Resistance Camouflages Genocide in Colonial Histories.” In Andrew Woolford, Jeff Benvenuto, and Alexander Laban Hinton, editors, Colonial Genocide and Indigenous North America. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

Parrish, J.L. “Anecdotes of Intercourse with the Indians.” Salem, Oregon, 1878. Microfilm manuscript, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Riddle, Jeff C. The Indian History of the Modoc War. Eugene, Oregon: Urion Press, 1974; originally published in 1914.

Thrapp, Dan L. Dictionary of Frontier Biography. Volume 3. Glendale, California: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1988.

Victor, Frances Fuller. “A Knight of the Frontier.” The Californian: A Western Monthly Magazine, vol. 4, no. 20 (August 1881).

“Verified Statement of W.T. Kershaw.” November 21, 1857. Oregon and Washington Volunteers, House Miscellaneous Document No. 47, 35th Congress, 2nd Session.

Wells, Harry L. History of Siskiyou County, California. Oakland, California: D.J. Stewart & Co., 1881.

Wells, Harry L. “The Modocs in 1851.” The West Shore, vol. 10, no. 4 (April 1884).

Centuries of Genocide: Modoc Indians, Part I

This story was originally published February 23, 2016.

© 2017 Indian Country Today Media Network, all rights reserved. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com

https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/history/events/the-indian-killer-dubbed-knight-of-the-frontier