With New Zealand’s Southern Alps looming above, about 30 members of the Winnemem Wintu tribe from Northern California sat on the windswept bank of the Rakaia River cradling in their hands dark and wormy salmon fry, a long-lost relative finally found.

As they released the salmon into a gurgling rivulet, a couple of Winnemem broke down in tears while others began softly singing a prayer song, barely louder than the breeze.

“I want you to have this relationship with the salmon, to have this in your hearts,” said Traditional Chief and Spiritual Leader Caleen Sisk. “So you’ll understand why we’re going to do whatever it takes to bring them back.”

That was on March 26, 2010. Now, seven years later, and after 80 years of separation from their salmon, the Winnemem Wintu are poised to receive a $200,000 grant this fall from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to begin the first phase of returning the the genetic descendants of their salmon home from New Zealand.

The grant will be used to fund the collection of tissue samples of the New Zealand salmon, which will then undergo DNA testing in the United States at the University of California, Davis. While records indicate the New Zealand salmon runs were created from eggs shipped from the McCloud River, government biologists remain skeptical about introducing the fish into California water’s systems.

“It’s amazing that our prayers have been finally answered after all these years,” Sisk said. “Our salmon in New Zealand are wild and spawning in the high mountain rivers; they’re the fitter, stronger salmon who are more likely to make it the hundreds of miles upriver through the canyons and waterfalls to the McCloud.”

The tribe has also sparked a viral social media campaign to bring the salmon home, through a GoFundMe that has raised more than $57,000 since June 6 and has drawn online support from prominent leaders throughout Indian Country such as Winona LaDuke, Pua Case and Dallas Goldtooth. Native musician Nahko Bear, inspired by the Winnemem’s commitment to their salmon, has helped produce a short documentary, Salmon Will Run, with Survival Media about the project and is holding benefit concerts throughout the summer for the salmon’s return.

Marc Dadigan

Indigenous musician Nahko Bear, Manua Kea Protector Pua Case and Winnemem Wintu Cultural Preservation Officer Pom Tuiimyali during the closing ceremony of the 2016 Run4Salmon.

“It’s the Winnemem Wintu’s right to exist and the right of an ecosystem to live,” LaDuke says in the film. “To stand with the Wintu is really important to me as a spiritual being and as a beneficiary of this ecosystem, but it’s also a chance to do the right thing.”

For millennia, the Winnemem’s salmon thronged in the McCloud River by the thousands and were a vital food source and presence in the tribe’s spiritual and ecological worlds. But the salmon have not returned since World War II, when the 600-foot Shasta Dam was erected, flooding 27 miles of the tribe’s homelands and leaving many Winnemem homeless.

Yet unknown to the Winnemem Wintu until 2004, the McCloud River salmon had persisted in the Rakaia River, where healthy and thriving year-round salmon runs were created from salmon egg shipments sent from the federal Baird Hatchery on the McCloud River in the 1890s and 1900s.

The Winnemem efforts to return their salmon coincide with a dire time for California salmon. Tribal fisheries on the Klamath River were shut down due to the low projected numbers for the spawning runs, and only 1,500 winter-run salmon returned to the Sacramento River in 2016. Some environmentalists say a recent federal analysis indicates Governor Jerry Brown’s proposed $17 billion Delta Tunnels (known as California Waterfix) would all but guarantee the extinction of salmon by diverting even more water from the Pacific coast’s largest estuary, a vital “nursery” for young salmon transitioning from freshwater to saltwater.

For salmon to survive climate change and deteriorating river conditions, a 2009 federal biological opinion declared salmon must return to the glacial waters above Shasta Dam where the cold water would allow their eggs to survive.

Courtesy of Moving Image Productions

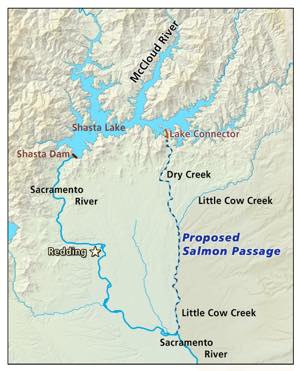

A map of the Winnemem Wintu’s proposed swimway for the salmon to travel around Shasta Dam.

The Bureau of Reclamation is overseeing the project to reintroduce salmon above the rim dams, and the Winnemem submitted a comprehensive plan to develop a swimway around Shasta Dam using natural creeks so the fish can re-establish a natural life cycle without human intervention.

However, an inter-agency Shasta Dam Fish Passage steering committee organized by the Bureau, from which the Winnemem were excluded, unveiled its own $16 million plan to employ a controversial “trap and truck” method to move Sacramento River hatchery salmon around Shasta Dam.

The Winnemem Wintu vehemently object to this plan, arguing that no truck and trap project has ever successfully reintroduced a salmon species and that the wild, disease-free salmon in New Zealand are far more likely re-adapt to the arduous 500-mile journey from the ocean to the McCloud River.

Louis Moore, Public Affairs Specialists for the Bureau, said there are a handful of successful trap and truck programs, such as on the Baker and Cowlitz Rivers in Washington State, that served as models for the Shasta Dam Fish Passage project. He also confirmed that Bureau officials agreed to allocate funds for the DNA testing and would consider, based on the results, bringing some New Zealand salmon to California to study how they adapt to California waterways.

“It’s early in the process, but the goal has always been to look at fish improvement and restoration on the river,” he said. “While there might be an opportunity to collect the fish and bring them back, the real work would be seeing how they respond once they get here.”

Also of concern for the tribe is a potential conflict of interest, Sisk said. The Bureau, which is overseeing the fish passage project, is also working with the powerful Westlands Water District on a proposal to raise Shasta Dam another 18.5 feet, which would inundate or impact more than 40 Winnemem sacred sites as well as prime salmon spawning habitat on the McCloud River. The $1.4 billion dam raise project, according to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife analysis, would also flood uncapped mines in the area, leading to more toxins and acid dumping into Shasta Lake, which is already labeled mercury-impaired by the state.

“The threats to our salmon are our pipeline,” Sisk said. “We have to stop letting these supposedly smart scientists manage our fish until they all die out. Our knowledge comes from generations and generations of living in this ecological system, and it says to get out of the way and let the salmon live as Creator intended.”

© 2017 Indian Country Today Media Network, all rights reserved. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com

https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/environment/winnemem-wintu-salmon-home-new-zealand/