Rodeo-Chediski Fire underscored need to thin forest

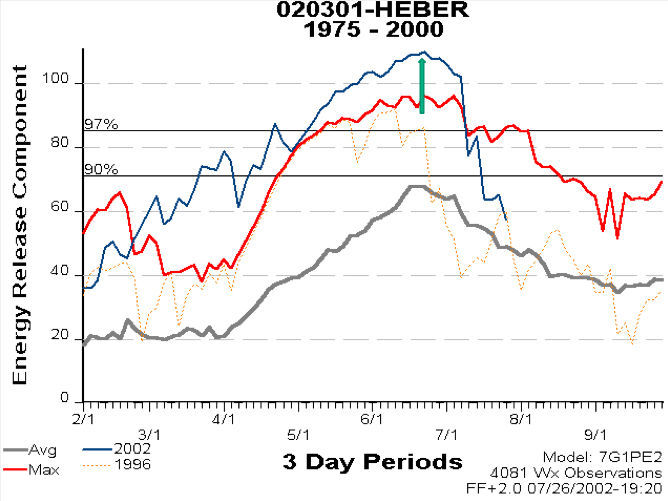

June 18, 2002 was statistically considered the single-heaviest fire currents day of the entire year.

That’s the day the Rodeo Fire started. Two days later, it became the Rodeo-Chediski Fire.

“It picked the worst day of the year that it could possibly find to start — and start, it did,” said George Leech, retired fire management officer from the Bureau of Indian Affairs-Fort Apache Agency and chief of operations on the Rodeo-Chediski Fire that consumed 468,638 acres of national forest and tribal lands by the time it was fully contained July 7, 2002.

It was, at the time, the largest fire in Arizona’s history and in the entire Southwestern United States — until the Wallow Fire surpassed it at 538,049 acres — across two states — almost a decade later.

“The one thing that’s interesting … when you look at the Rodeo-Chediski Fire and the Wallow Fire — the Wallow Fire ended up a little more than half a million acres and took it something like six weeks,” Leech said. “The Rodeo-Chediski Fire wound up a little under half a million acres — 470,000 — and it did that in six days.

“That tells you which one was rompin’ and stompin’ and takin’ names.”

Speaking of names …

The Rodeo-Chediski Fire was the result of two separate blazes combining into one. The Rodeo Fire was so named because it started near the Rodeo Fairgrounds in Cibecue. The Chediski Fire started a couple of days later over by what’s known as Chediski Peak near Heber/Overgaard.

The Rodeo Fire started after Leonard Gregg, a member of the White Mountain Apache Tribe and a seasonal firefighter, set two fires on the morning of June 18, 2002, in the hopes it would land him some work with the BIA as part of a quick-response fire crew. The first fire was the Pina Fire, about 3½ miles away from where he started the second blaze that grew into the Rodeo Fire.

The Pina Fire was quickly extinguished until crews fighting that fire were called to the Rodeo Fire.

Gregg admitted to using wooden matches to set the dry grass on fire and said he expected to work with the fire suppression team for a day. A story published in the Sonoran News states Gregg “never expected the fire to develop into what it did.”

Gregg was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison on two counts of arson. He served nine years and was released June 17, 2011. As part of his sentence, Gregg was ordered to pay $27.9 million in restitution.

“Unfortunately, it was someone I trained,” Leech said.

Two days after Gregg started the Rodeo Fire, Vallinda Jo Elliott, a stranded hiker, started what evolved into the Chediski Fire after she became lost in the wilderness. After seeing a news helicopter from a Phoenix television station fly overhead, she lit a signal fire. She had been stranded for about three days — after her car ran out of gas — when she spotted the news helicopter flying overhead toward the Rodeo Fire.

“The stuff she had to survive on was two cigarettes and a lighter,” Leech said.

Elliott was rescued, but the fire she started eventually merged with the Rodeo Fire and burned almost 470 homes.

Elliott was not charged with arson, but a judge in 2009 ruled that the White Mountain Apache Tribe could sue Elliott in tribal court for civil damages.

In 2014, nearly 12 years after she ignited the Chediski Fire, the Office of the Attorney General for the White Mountain Apache Tribe secured that civil judgment. The tribal court found Elliot’s acts in igniting the Chediski Fire “grossly negligent and reckless,” thereby ordering her to pay $1,650 in civil penalties and $57 million in restitution to the tribe.

Leech said he went to inspect the area where Elliott started the Chediski Fire and what he found surprised him.

“Knowing what I know about fire, if I had to pick a spot that would be safe, I would have picked the spot that she did,” he said. “It was a talus slope (the accumulation of broken rock or other debris at the base of a cliff or other high place), a little bit of grass — and that was it. It was about 75 yards from the nearest tree. There wasn’t anything in there. But it managed to get out and started the Chediski Fire.”

The two burning areas joined on June 23, 2002, thus becoming the Rodeo-Chediski Fire.

Quick-moving fire

A day after the Rodeo Fire started, talk of evacuations of nearby towns – Show Low, Pinetop-Lakeside, Linden, Clay Springs, Pinedale and others, began. Winds of 20-25 mph earlier that day turned what was a ground fire into what’s called a high-intensity crown fire – one that spreads from treetop to treetop. It’s also burning through established fire-retardant lines and “throwing” ash and embers out in front of it, thus starting more fires.

By 10 a.m. June 19, the fire had crossed Carrizo Canyon, a traditionally wet drainage that was thought to be protected from the wind.

“There was also a road in there, but the fire crossed all of it like it wasn’t even there,” Leech said.

Five air tankers and one heavy air tanker performed futile efforts to get ahead of the fire.

“There was stuff falling out of the sky every 3-4 minutes,” he said. “It was like fighting mosquitoes; (the fire was) all over the place. In three minutes, they not only lost the fire, but it spotted across and burned through a fire line onto the other side. In 3-4 minutes, the fire is burning something like 150 yards. You can hardly walk 150 yards (in rough terrain) in that length of time. That tells you some of the intensities we had.”

During a 30-minute period, Leech said the Rodeo Fire grew from about 25,000 acres to more than 55,000 acres.

“Let me put that in terms that we can all relate to a little bit better,” he said. “You’re out on the highway. You have a mile-wide fire on the right side of the road and a mile-wide fire on the left. You and fire are all headed in the same direction. At 60 mph, you are staying even with it — and you’re doing that for 30-45 minutes. That’s like driving from (Fool Hollow Lake in Show Low) to the north side of Snowflake.”

The average speed of the Rodeo Fire, he said, was about 5,600 acres per hour — almost 100 acres per minute, or 9 square miles per hour.

Creating its own weather

Because of its intensity, the Rodeo Fire started creating a distinct weather system, Leech said, through its own plumes of smoke.

“It became a plume-dominated fire,” he said. “The smoke plumes rotate and wrap underneath – basically a convection column. It takes a tremendous amount of heat for that to happen. It doesn’t happen under light fuels. It has to be heavy fuels, it has to be an intense fire, and because it was happening at 20-25 mph, it was beyond amazing.”

Leech said more forest acres were burned on windy ways of 20 mph than on windy days of 30 mph.

“At 30 mph, it was enough to break those plumes apart,” he said.

These plumes reached about 40,000 feet into the air – high enough to be captured by satellite photography. Above the plumes, Leech said, were ice crystal formations — also known as palieus clouds — that formed a halo effect.

“When you see ice crystals forming on top of a cloud, no matter if it’s a thunderstorm or a cloud of smoke, there’s very cold air up above — and cold air is heavy — and it will come back down through the fire, through the (smoke) column at some point and hit the ground at 70, 80, 90, 100 mph. They would last between 5-15 minutes.”

When these columns of cold air collapsed and hit the ground at those speeds, Leech said it had the power to move an entire wall of fire, or even a finger of the fire, “in any direction it wants.”

“Generally speaking, these microbursts would move the fire about 3-5 miles in a 10-15 minute period,” he said. “That’s like trying to stop a runaway freight train with a ping-pong ball.”

Over the next few hours, more of these plume columns developed and the Rodeo Fire turned into a “pulsing plume-dominated fire,” in which several of these columns simultaneously build and collapse.

“We had five of these pulsing plumes, on average, over the top of the Rodeo Fire throughout the first day,” Leech said. “As the fire grew, so did the number of pulsing plumes.”

Fire intensity

By 4 p.m. June 19, flame lengths were recorded at about 1,500 feet. During one harrowing helicopter ride around the fire meant to map its march, Leech said the flames reached as high as he and the pilot were flying – between 1,200 and 1,500 feet above the ground.

“The turbulence was enormous. I didn’t have on my spurs and my seat belt was cinched another three notches — and it was all we could do to stay in the seat,” he said. “The pilot didn’t like it any more than I did.”

Large burning gas balls intermittently shot into the air “like exploding fuel trucks,” Leech said. He added that the fire was so hot, large rocks within the fire exploded “like firecrackers going off.”

Leech said had the Rodeo Fire been wind-driven, it would have been much easier to manage.

“The thing about a plume-dominated fire is you have absolutely no idea where it’s going, how fast it’s going to get or what it’s going to do,” he said. “They are absolutely, completely unpredictable. The nice thing about a wind-driven fire is, you can’t do anything with it but at least you know where it’s going.”

The aforementioned plume-domination effect from both the Rodeo and Chediski fires eventually pulled one into the other.

“Big fires pull small fires into it,” he said. “From 20 miles away, they’re pulling each other together.”

Radiant heat

The Rodeo Fire burned so hot, Leech said, that it took out the root systems of any living thing in its path.

“Anything that had any mass to it, it just completely consumed within just a few minutes,” he said. “It melted T-posts (a rail steel fence post) in multiple places within the fire. Those are not easy to bend, let alone melt.”

Not all tree stands within the fire burned. According to Leech, many survived the initial wave of fire that swept through many areas, only to die because of the intense heat radiating from white ash material, mostly burned-out logs and old trees layering the forest floor.

“The fuel moisture in this material, usually about 18-20 inches in diameter, was in the 3-4 percent range. That’s less than the humidity in your house in the middle of winter,” he said. “When it’s very dry like that, they contribute to the flame in front of the fire, which increases the intensity, which causes plume domination.

“Also, the large diameter material takes a long time to burn out. The radiant heat that comes off that big material is enough to kill and cook pretty much anything. There might be one or two trees still standing out there, but I doubt it. If the fire didn’t crown out, the radiant heat killed the rest.”

Lop and scatter

In the years before the Rodeo-Chediski Fire, the Forest Service practiced what is known as “lop and scatter,” in which slash was cut to about 16 inches above the ground and left lying on the forest floor. The thought was the slash and other material left on the ground would rot and provide a sort of fertilizer for the healthy tree stands.

“But when the fire came through, (the U.S. Forest Service) found out that it didn’t rot. The areas of high-intensity burns occurred through a lot of the thinned areas that were lopped and scattered. Lop and scatter doesn’t work. You must follow it up with fire.

“(Prescribed burning) creates a lot of smoke and inconvenience for many people living in the area, but the alternative isn’t very good.”

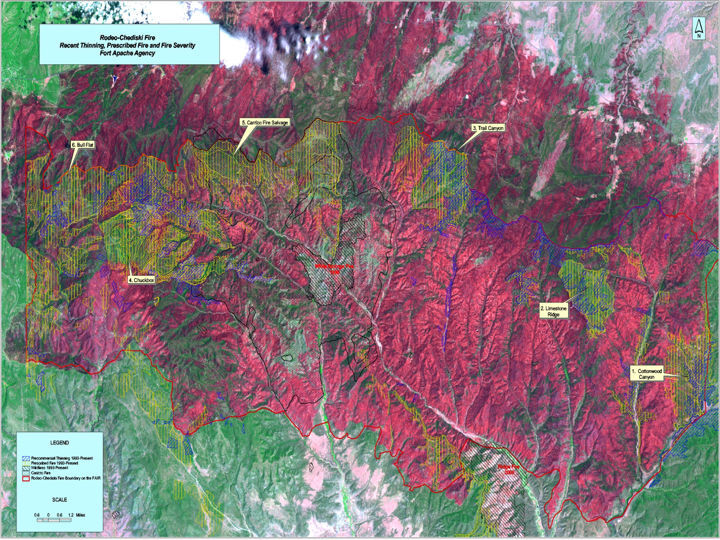

In the Chediski portion of the fire, Leech said there was one thing working in firefighters’ favor: The timber-laden area had seen a “fair amount” of logging, thinning and prescribed burning activity in previous years.

More evacuations

Leech said that if the Rodeo Fire reached Hop Canyon, another round of evacuations would be ordered. On June 22, 2002, it reached the canyon.

About 30,000 residents and “twice as many visitors” were evacuated from Show Low, Pinetop-Lakeside, Linden, Clay Springs and other areas. Heber/Overgaard on the west end of the Rodeo-Chediski Fire had already been evacuated, Leech said.

Many people fled to nearby communities that welcomed them with open arms. Residents in Holbrook, Snowflake, Taylor, St. Johns and Springerville/Eagar all opened their doors to provide shelter for those escaping evacuated areas.

On June 25, the fire reached Cottonwood Canyon, the site of logging, thinning activity and previous prescribed burning.

“The closest the fire came to Show Low was Bison Ridge,” Leech said, “about 400 feet from getting in. Talk about luck. How on earth we did it, I don’t know.

“This fire almost made the Taylor-Snowflake area, believe it or not.”

Security

With a major evacuation comes huge security issues.

“We had more police on the mountain during that week-and-a-half or two weeks than there ever has been or ever will be,” Leech said. “Security is an issue because when you evacuate the people, you must provide for security of their property.”

Many in law enforcement, as well as the U.S. Forest Service, patrolled the evacuated municipalities, with some working their normal shifts, then volunteering to help keep the evacuated communities secured during their “off” hours.

The ‘white’ in the White Mountains

Historical U.S. Army cavalry documents from the 1890s state a unit was on patrol along the rim through the White Mountains. It tells of the forest and its condition at the time, stating that soldiers rode for three days “through a burned area” — most likely a recent forest fire — and adding, “there is no feed for our stock.”

“Fires here burn incessantly, from early spring until snow. The air is always white with smoke,” the document states.

“There’s a reason why it’s called the ‘White Mountains,’” Leech said. “It’s not snow, it’s white air from the smoke all the time.”

Forest management legislation

The Rodeo-Chediski Fire helped kick-start new forest management laws that were enacted by Congress, including the Healthy Forests Restoration Act, which is intended to reduce the threat of destructive wildfires by allowing timber harvesting on protected national forest lands. President George W. Bush signed it into law in 2003.

Leech said there are three essential ingredients for a healthy forest: Rain, snow and fire.

“You know what happens if you take rain and snow out of the environment. It all goes downhill really fast,” he said.

Leech said fire history obtained from tree ring data in the White Mountains and Mogollon Rim, stretching from New Mexico to the Kaibab National Forest, shows fire intervals of three to five years.

“The only way you can get a fire to repeat — in some cases it’s actually almost annually — that frequently is if you have a lot of grass cover,” he said. “At three- to five-year intervals, you’re going to have very little fuel, an extremely healthy forest and extreme biodiversity; we’re talking literally hundreds of different plant and animal species.”

Leech said taking fire out of the equation is “more insidious” in that the effects are not immediately shown.

“It doesn’t show up today, it doesn’t show up next year. It shows up 20, 30, 50, 100 years from now,” he said. “Fire suppression has been going on since the early 1920s, so we’re just teetering at 100 years. You look at fire behavior in the forest, everything has, because of fuel loading, reached critical mass. It’s not sustainable the way it is.”

“If we don’t do something with it, it will burn.”

Michael Johnson

Editor

Michael Johnson is the editor of the White Mountain Independent.

Copyright 2016, White Mountain Publishing LLC, Show Low, AZ.