Seth Jones, who is Te-Moak Western Shoshone, doesn’t just make stone blade knives, he uses them. He also likes to know that people who acquire them will put them into service. “I don’t want to think of my knives sitting on a shelf,” he said. The items are practical, with blades that can be sharpened or replaced. If he needs a knife and happens not to have one with him, he makes one.

The first time Jones used a friend’s stone-bladed knife—to dress an elk—he was hooked. “Skinning is not only faster than with a steel knife, you come away with a beautiful hide without holes,” Jones said. “In contrast, a steel knife can slice through a hide with one misplaced swipe.” Then there was the trip to Crow Agency, when he and his father—using stone blade knives—finished dressing a buffalo cow before three other hunters completed a calf.

Jones has made a study of the ancient technology, so he can understand how it was—and is—so effective. “I’ve learned that flint-knapped blades can be sharpened more finely than steel scalpels and can even slice an individual cell in half,” he said. Surgeons have noticed. Bruce A. Buck, MD wrote in the Western Journal of Medicine that stone scalpels make cuts that are less painful and less likely to cause infection; they also result in a thinner scar.

A Canadian physician regularly uses stone blades for surgeries, he told CNN Health in 2015. He is part of a long tradition. Peruvian doctors used stone blades for cranial surgery at least 1,000 years ago, according to bioarchaeologist Danielle Kurin, writing in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. The technique was known in Mexico of that era, as well as in China 7,000 years ago and in France 8,500 years ago.

Some of Jones’s stone blade knives are flint-knapped (chipped from a larger piece, then shaped) and tied with sinew to antler or wooden handles, as his ancestors might have done. They were the Tosawi, or White Knives Band, famed for the super-sharp white-flint knives they carried.

Other items Jones produces are contemporary, including pocketknives with a stone blade that hinges around a copper rod to fold into the antler handle. He also works with thin slices of mirror that he epoxies back to back, then flint-knaps to create an elongated shape and ridged surface similar to a traditional arrowhead; another artist uses them in beaded jewelry. Jones shows off their glitter, calling them “better than diamonds.”

Courtesy Seth Jones

Seth Jones made this pocketknife with an obsidian blade that folds into an antler handle. Jones makes stone blade knives that he uses and sells.

Courtesy Seth Jones

Seth Jones’s latest breakaway pocketknife design updates ancient technology for modern needs, with a super-sharp chert blade folding into an antler handle via a brass hinge. Jones makes stone blade knives that he uses and sells.

The 33-year-old father of three helps manage his family’s Elko, Nevada construction company. That’s when he is not out on the land looking for interesting stone to put in virtuosic silver settings. He has been a rock hound for as long as he can remember and a flint-knapper since he saw a demonstration in the third grade. About a dozen years ago, he started using the exceptionally hard white flint, or chert, that his ancestors favored.

In his research, Jones learned that his ancestors made chert easier to work by heat-treating it. His first effort was unexpectedly exciting. He put a chunk in the oven and soon heard a loud blast. When he opened the door, he found the chert had shattered into small pieces. He realized that heating it too rapidly had caused the water droplets trapped inside to expand quickly and produce an explosion.

Now, Jones uses a kiln to heat his stone slowly, increasing the temperature by 50° F per hour until it reaches 500° F or higher, depending on the material. He maintains the stone at the high temperature for a few hours, then allows it to cool equally slowly.

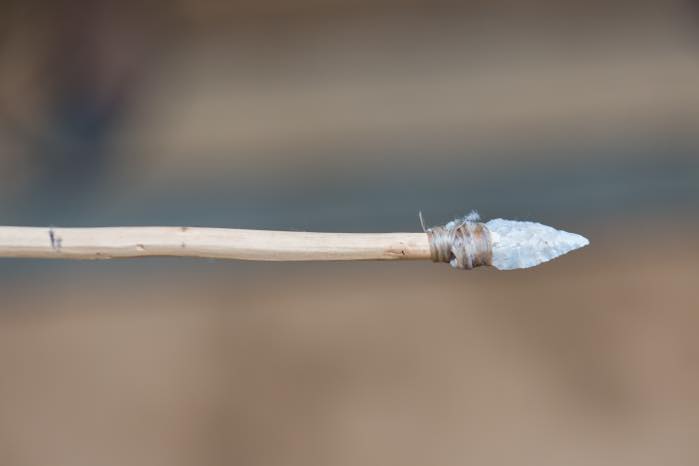

Photo by Joseph Zummo

A chert-tipped arrow made by Seth Jones. Jones makes stone blade knives that he uses and sells.

When creating arrow and spear points, Jones said, the maker considers interdependent requirements—the length and weight of the bow and the shaft, the type of wood used, the game the hunter will seek and other factors. The point or blade is attached to the shaft or handle with sinew saved from hunts, dried for a few weeks then pulled into separate fibers. Chewing on the fibers moistens them and activates their natural glue for a tight, strong wrap.

Everything in this process has to mesh perfectly for the hunt to succeed. “Their lives depended on it,” Jones said of his ancestors. But style was also important to them. “I can see that they weren’t stamping them out,” Jones said about ancient weapon points and other items he has seen in the field.

Working stone has taught Jones to read ancestral landscapes, like the pages of a vast natural book. “Where I grew up, north of the Tosawihi Complex, you can see where they found game and where they repaired used arrows,” he said. “When shooting game with a flint arrowhead, it can hit a rock or bone and the tip can break off. So around springs, where hunters found game that had come to drink, you find broken tips.”

In other places, Jones has sighted scrapers, stone drills and the back halves of arrows—the portion that was attached to the shaft. “These were camps, where they returned to process what they had hunted and to repair their arrows. A shaft was valuable, so you wouldn’t discard it when its point broke. You’d bring it back to camp, unwind the sinew securing the broken half and put on a new arrowhead.”

Photo by Joseph Zummo

Renowned Western Shoshone basketmaker Leah Brady looks at a chert-tipped arrow made by Seth Jones. “I like to acquire things I admire,” Brady said. Jones makes stone blade knives that he uses and sells.

The raw material for these items had a life cycle, Jones said. Carrying around big heavy chunks of rock would have been inefficient, so the hunter chipped off and heat-treated a rounded piece that was an inch or two thick and about the size of a pancake. This “biface,” as it is now termed, could be used as is, to saw bone, for example.

It could also be cut into smaller tools and weapons. The tool kit for working the biface would have included a heavy piece of antler for knocking off pieces, along with antler tips for pressure-flaking (pressing down on the edges and sharpening them). Some articles would have ended up with scalpel-like edges, while others had serrated edges.

Jones recalled reading an ICMN story about artifacts that archaeologists had scooped into boxes and stored in a museum. He felt, like fellow tribal members quoted in the story, that this destroys evidence of their history and connection to the land—a huge range of subtle and detailed information that they are best qualified to observe and to comprehend.

See more of Jones’s work on Instagram. You’ll see photos that he and other artists have posted and can contact him there. Jones’s stone blade knives, including a sharpening tool kit, run between $200 and $1,500 depending on the materials and the complexity of manufacture and design.

© 2017 Indian Country Today Media Network, all rights reserved. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com