When the Idea of Home Was Key to American Identity

From log cabins to Gilded Age mansions, how you lived determined where you belonged

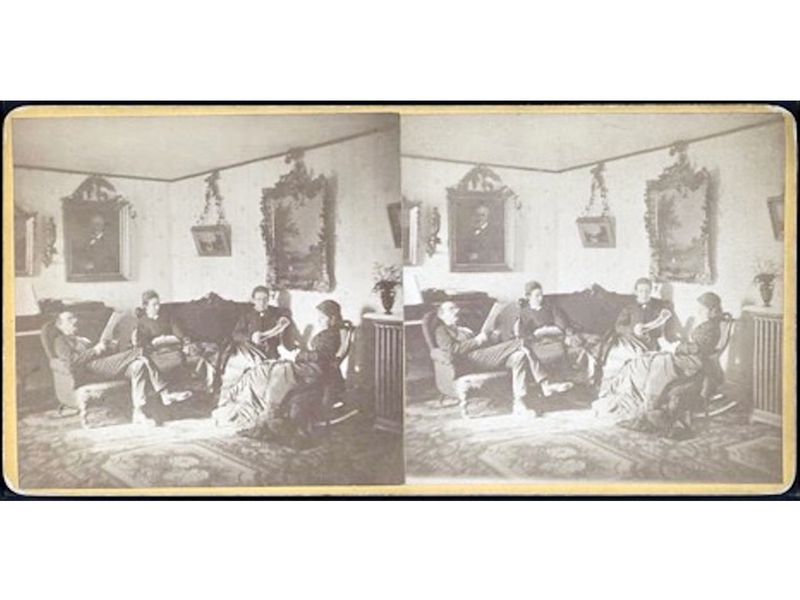

Like viewers using an old-fashioned stereoscope, historians look at the past from two slightly different angles—then and now. The past is its own country, different from today. But we can only see that past world from our own present. And, as in a stereoscope, the two views merge.

I have been living in America’s second Gilded Age—our current era that began in the 1980s and took off in the 1990s—while writing about the first, which began in the 1870s and continued into the early 20th century. The two periods sometimes seem like doppelgängers: worsening inequality, deep cultural divisions, heavy immigration, fractious politics, attempts to restrict suffrage and civil liberties, rapid technological change, and the reaping of private profit from public governance.

In each, people debate what it means to be an American. In the first Gilded Age, the debate centered on a concept so encompassing that its very ubiquity can cause us to miss what is hiding in plain sight. That concept was the home, the core social concept of the age. If we grasp what 19th-century Americans meant by home, then we can understand what they meant by manhood, womanhood, and citizenship.

I am not sure if we have, for better or worse, a similar center to our debates today. Our meanings of central terms will not, and should not, replicate those of the 19th century. But if our meanings do not center on an equivalent of the home, then they will be unanchored in a common social reality. Instead of coherent arguments, we will have a cacophony.

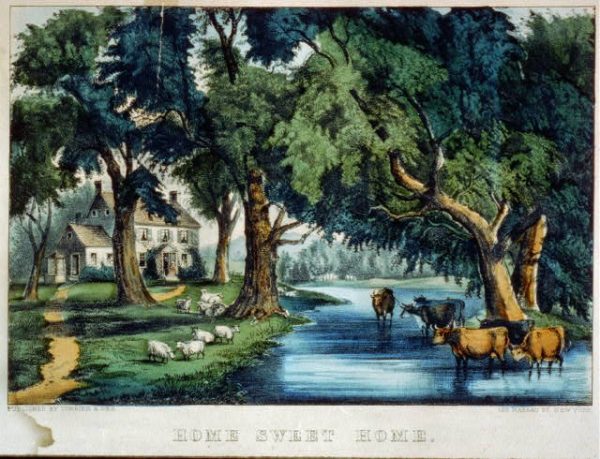

When reduced to the “Home Sweet Home” of Currier and Ives lithographs, the idea of “home” can seem sentimental. Handle it, and you discover its edges. Those who grasped “home” as a weapon caused blood, quite literally, to flow. And if you take the ubiquity of “home” seriously, much of what we presume about 19th-century America moves from the center to the margins. Some core “truths” of what American has traditionally meant become less certain.

It’s a cliché, for example, that 19th-century Americans were individualists who believed in inalienable rights. Individualism is not a fiction, but Horatio Alger and Andrew Carnegie no more encapsulated the dominant social view of the first Gilded Age than Ayn Rand does our second one. In fact, the basic unit of the republic was not the individual but the home, not so much isolated rights-bearing-citizen as collectives—families, churches, communities, and volunteer organizations. These collectives forged American identities in the late-19th century, and all of them orbited the home. The United States was a collection of homes.

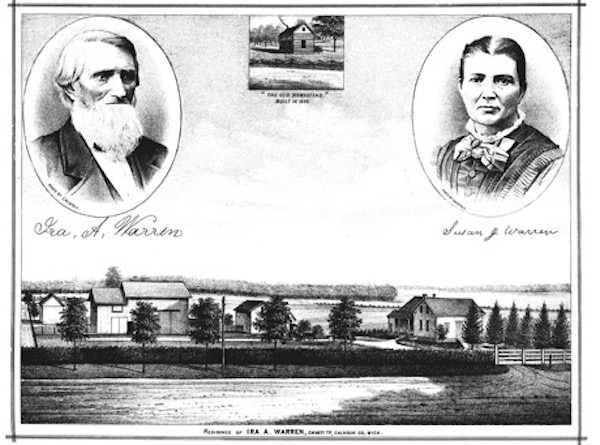

Evidence of the power of the home lurks in places rarely visited anymore. Mugbooks, the illustrated county histories sold door to door by subscription agents, constituted one of the most popular literary genres of the late-19th century. The books became monuments to the home. If you subscribed for a volume, you would be included in it. Subscribers summarized the trajectories of their lives, illustrated on the page. The stories of these American lives told of progress from small beginnings—symbolized by a log cabin—to a prosperous home.

image: https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/96/9d/969d6e9d-7323-4e11-a768-22f527880a18/white-wimtba-on-home-image-3-1.jpg

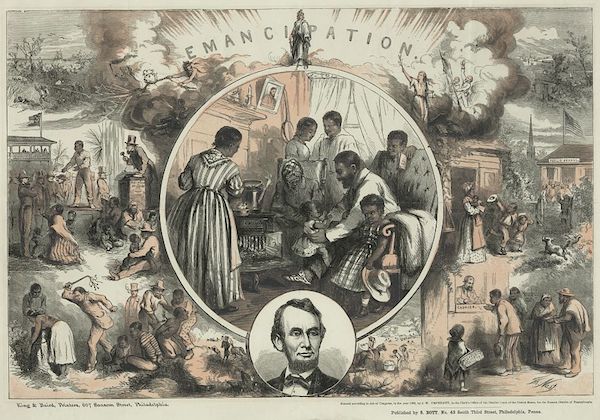

The concept of the home complicated American ideas of citizenship. Legally and constitutionally, Reconstruction proclaimed a homogenous American citizenry, with every white and black man endowed with identical rights guaranteed by the federal government.

Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-idea-home-was-key-american-identity-180964892/#Hw42yhlVTWCjv32X.99

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter