Currents in a Cul-de-Sac

Bob Carney

Louisiana State University

We are all familiar with cul-de-sacs— neighborhoods where you have to turn you car around to get out. The circulation of the Gulf of Mexico

and Caribbean is similar to a cul-de-sac. Because ocean life depends

on currents to transport larvae, it is possible that the Gulf’s fauna

may be controlled to some extent by these unusual current patterns.

turn you car around to get out. The circulation of the Gulf of Mexico

and Caribbean is similar to a cul-de-sac. Because ocean life depends

on currents to transport larvae, it is possible that the Gulf’s fauna

may be controlled to some extent by these unusual current patterns.

Gulf Surface Currents

Surface currents are ocean currents in which the moving water lies

between the surface and a maximum depth of about 500m. Currents that

are no deeper than 200m are usually caused by the wind pushing on the

water. Currents as deep as 500m usually are caused by forces

associated with the rotating Earth and are called geostrophic

(Earth-turned) currents. In our exploration of the Gulf of Mexico we

are concentrating our research on the ecology below 500m and are very

interested in the Gulf Loop, an example of geostrophic flow that

strongly influences our exploration area.

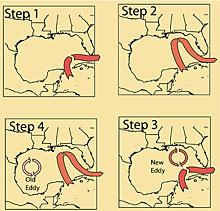

The Gulf Loop flows in through the straits of Yucatan and exits

through the straits of Florida. Sometimes it is confined to the coast

of Cuba. At other times, it flows along a long loop to the North

before turning south and eventually exiting through the straits of

Florida. This elongated loop is unstable and pinches off large eddies

that spin clockwise as they drift westward. The eddies eventually spin

down in the western Gulf. They sweep over the bottom and may have a

great influence on the ecology.

|

|

|

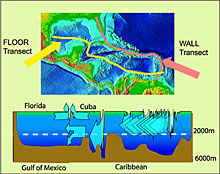

The general

current flow of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean is

greatly influenced by the narrow gaps in the eastern wall

and by the depth of inter-basin sills. This can be seen by

examining bathymetry of two transects. Click image for

larger view and expanded caption.

|

|

|

Gulf Deep Currents

We know little about circulation below 500m, but we are studying it

extensively at this time. We do know, however, where the deep water

enters the Gulf. This information leads us to suspect that animals in

the Gulf may be somewhat different than those in the adjacent

Atlantic.

The Gulf is rather isolated, and we know that it is 3600m deep. The

Yucatan Strait is about 2000m deep, but the Florida Strait is only

about 800m deep. This means that the deep water in the Gulf flows in

from the Caribbean, not directly from the Atlantic. In effect, the

islands of the eastern Caribbean form a very leaky wall with many

shallow gaps, but only a few deep gaps. Just as this wall limits deep

water flow, it might partially isolate animal populations in the deep

Gulf from the populations in the larger deep Atlantic.

Researchers at Louisiana State University (LSU) (Welsh, Innoue,

Wiseman, and Walker) and Texas A&M University (Nowlin) are actively

studying how the deep water circulates once it enters the Gulf, and

how it gets back out. So far much preliminary research has been

conducted using computer simulation and a few current meters placed

deep in the Gulf. In 2003, this research will be greatly advanced when

many deep-sea instrument arrays will be installed by LSU, the offshore

oil industry, Mexican scientists and industry, and the US Minerals

Management Service. Once that operation has been completed, we will be

able to determine exactly how organisms are carried by currents across

the exploration area.

Dr. Susan Welsh of LSU has provided us with preliminary information

about the deep currents using computer simulations and a program

called the Modular Ocean Model. Her data indicate that in the

expedition area of the northern Gulf, the seafloor at 500-1000m

experiences average currents to the east at a mean velocity of 10

centimeters per second (cm/s). Deeper in the northern Gulf (2000m to

3000m) the currents reverse, nearly following the isobaths to the west

or southwest. The mean flow along the slope is closer to 5 cm/s. Off

west Florida, below 1000m, the currents flow to the north with mean

currents less than 10 cm/s, increasing with depth. Eddies are spawned

by the Gulf Loop eddies that are created with the general flow.

Apparently, these eddies can reach bottom speeds of up to two knots.

These spinning eddies move water across depths (up and down) of

several hundreds of meters and may be the source for transient high

velocity currents.

|

|