For a wonderfully complete and detailed history of the Colorado River Water agreements between the States please go to: http://ag.arizona.edu/AZWATER/arroyo/101comm.html the following is excerpted from this document.

Despite the objections the adopted strategy was to divide Colorado River water equally between Upper and Lower Basin states, with the demarcation line set at Lee's Ferry, located in northern Arizona's canyon country close to the Utah border. Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico were designated Upper Basin states and California, Arizona and Nevada Lower Basin states. Each basin was to receive 7.5 million acre-feet (maf) per year. Along with their allocations, the Lower Basin states could increase their apportionment by one maf. This represented a bonus to ensure lower basin acceptance of the compact

Colorado River water was apportioned, with California receiving 4.4 maf, Arizona 2.8 maf and Nevada 300,000 af, with each state also awarded all the water in their tributaries. Arizona was a big winner, gaining almost all the advantages it sought in the 1922 compact. A nagging water supply problem was resolved.

The Upper Basin states proved more amendable to a cooperative settlement. A contract was signed in 1948 assigning 51.75 percent to Colorado, 23 percent to Utah, 14 percent to Wyoming and 11.25 percent to New Mexico.

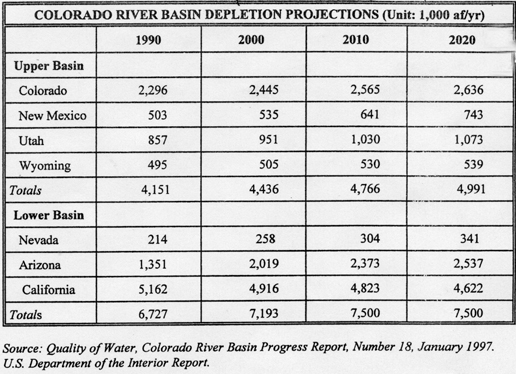

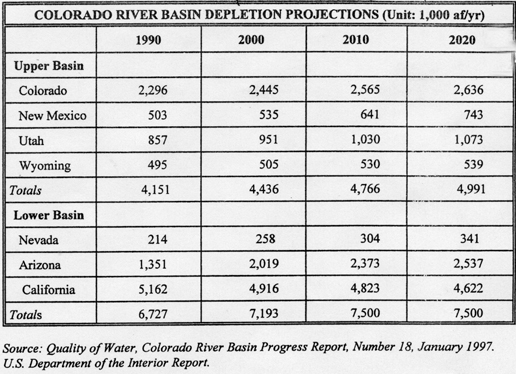

The states vary to the extent they are currently using their Colorado River allocation. Development is occurring much slower in the Upper Basin states than in the Lower Basin and as result Utah, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico have not yet used their full allocation of Colorado River water.

The rapidly growing Lower Basin states have a more immediate need of their Colorado River apportionments. Southern Nevada anticipates that the state's 300,000 af Colorado River allocation along with its groundwater resources will meet its needs only until about 2015. Officials are vigorously exploring options for obtaining more water, including dipping into Arizona's hitherto unused portion.

The Central Arizona Project was to enable Arizona to more fully use its full 2.8 maf allocation of Colorado River water. Transported CAP water, however, has not sold as readily as expected. As a result, Arizona in recent years still used only part of its allocation, leaving from 300,000 to one maf in the river.With the establishment of a water bank, Arizona is expected to use almost its full allocation for the first time this year. Before the water bank, the state did not expect to use its full allocation until the mid-21st century.

In this manner Colorado River water is shared and used. The system has worked up until now mainly because the states have not been using their full allocations. As each state's supply is fully appropriated the system will tighten. A milestone was reached in 1990 when Arizona, California, and Nevada consumed for the first time the total Lower Basin's 7.5 maf allocation.

Some, like environmental concerns, were not recognized as important at that time, while others, like Indian water rights, were simply side-stepped by compact negotiators.

1963 Supreme Court decision Arizona v. California the decision also quantified federal reserved rights of the five Indian reservations along the lower Colorado River: Chemehuevi, Cocopah, Colorado River, Fort Mohave and Quechan (Fort Yuma). Under this standard, five Indian reservations with a total population of about 10,000 were granted approximately 900,000 af of water. The lower Colorado River reservations presently are using about 80 to 90 percent of their entitlement.

Because of this landmark case these tribes have the best water rights along the Lower Colorado River. From neglected interests or parties, Indians became major players.

Still unquantified and conceded to be potentially huge, the Navajo Tribe's water rights claim could cut into the Colorado River apportionment of four states: Arizona in the Lower Basin and New Mexico, Colorado and Utah in the Upper Basin, with the major burden on Arizona.

Some officials have speculated on what the Navajo claim might be. Noting two such publicized figures, about two maf and five maf. One referred to the Navajo Tribe with its unquantified water rights as a "sleeping giant" and viewed Indian water right claims as possible "compact busters."

In the matter of water transfers, tribes generally view themselves as sovereign entities, not unlike states. Gary Hansen, attorney for the Colorado River Indian Tribes, said that, under the Winter's Doctrine, tribes have complete control of all beneficial uses of their land and water. Tribes therefore have the right to lease their water to interested entities, without the interference of the states in which their reservations are located.

Prompted by the federal action the Arizona Legislature in 1995 created a state water bank. The bank serves several purposes. For one, it is a strategy for Arizona to secure the unused portion of its 2. 8 million acre-foot Colorado River allocation.

Arizona feels very protective about its unused Colorado River allocation, aware that thirsty California and Nevada have designs on it.

Arizona's water bank is to save some of that water for use in the state. Plans call for 260,000 af of Colorado River water to be delivered via the CAP aqueduct to central and southern Arizona, for underground storage in existing aquifers or to be exchanged with water districts that pump groundwater. Along with storing the state's unused Colorado River allocation, the Arizona water bank also provides water storage services to California and Nevada.

Water shortages were not on the minds of compact negotiators; in fact, they seemed to believe that surpluses were more likely. As a result, the compact does not include provisions to deal with shortages due to drought. A prolonged drought, however, would strain the entire system. Who then has priority water rights from a drought-stricken Colorado River? This is a debated issue.